Read more

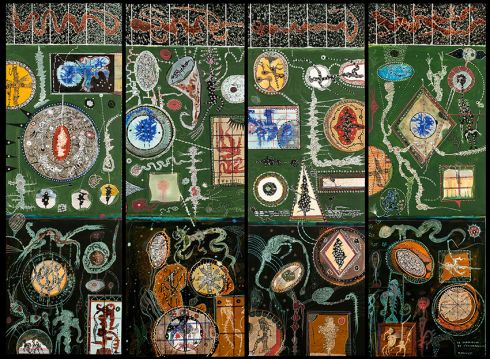

(Algiers, 1952)

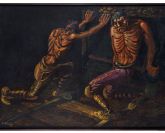

The Sleep of the Carbuncle

Undated

Polyptych of four panels on paper, marouflaged on card and glued on a stretcher

Acrylic, various inks, coloured pencils

120 x 160 cm

Signed and titled lower right: LA DORMITION / DE L’ESCARBOUCLE / B. PRUVOST

I do believe that this scene, the scene I am on the point of sha- ring with you, like a whole raft of others, often identical or almost identical, is to be found in a place – my studio, shall we say – where the light (like that of a momentarily diaphanous ceremony) is close to the dimness of shadowy uncertainties. What yokes them together will be paper or canvas.

For the moment, I stand in livid silence on the barren threshold of the undefiled paper on the table. With a pleasure tinged with trepidation, I anticipate beginning to populate and bring life to this deserted land. Suddenly I have created an incident.

Another sweatingly hot day and I lean over the unrolled paper to admire its grain and appreciate the sensuality of it under my fingertips. Suddenly, two beads of perspiration fall from my forehead and form rings on the paper. I immediately add a few drops of ink into the aquatic misadventure and in no time they turn into the outlines of winged creatures of some sort with countless limbs. It is the beginning of a painting, carried out under the serendipitous influence of random chance. Thus begin the marriage celebrations of not obviously marriageable things. A short while later adulterated elements of the human pantomime, a host of faunlike illusions, conceived and dancing in a gaudy sprawl of colours, twist and turn in every direction, including the most unexpected. Moods from some wild source are borne along another slope by the illuminating lanterns of chiaroscuro, under the vacillating shadow of floral, mental, comical or funeral postures, hilarious or fatal gesticulations.

It is beginning to seem as if the painting is perhaps taking on the appearance of completion, swept along on the river of the irrational, which floods it with hybrid forms or missteps, hesitating between human, animal, vegetable and mineral, the aquatic and the aerial, the cosmic and the organic.

This is the way it usually comes about.

Sometimes I draw up a vague plan, a few sketches, but everything is invariably brushed aside, thrown out of the window and changed around until it is unrecognisable.

To begin with I create a random event. It might be a stain, a splash of pure or diluted colour, or even the sketch of a design created by some chance manoeuvre. (This can take place anywhere on the paper).

This is when the anchor is weighed and the adventure begins. This is the starting point, the detonator from which all sorts and kinds of painting deeds flow after, into and out of one another.

After a few hours, a few days, a few weeks, the paper which had once been the chaste kingdom of the abhorred vacuum begins to fill up, to be traversed by amazing events and mental agita- tion. It has turned into a stage filled with pure inventions. The curtain is raised to reveal extravagant goings-on in all directions, clothed in rags and shivering dances: for the moment I am the only person in the audience for the first act of this performance. Every time I contemplate what has come into being, and see everything that has crowded into an unknown space, it seems to be the result of some amazing enchantment that propels me into a unique category of trance, a magical twist of the mind that has nothing in common with intoxication of the Bacchic or cannabis-induced kind. It is a cohort of sensations that sails off into uncharted waters.

Every time anyone asks me why I paint, which people often do, I always tell them that I paint solely for the intense pleasure of doing it, of indulging in this extraordinarily exciting activity. There is not the slightest doubt about it, the long years that I have happily devoted to painting have in no way dampened or diminished my infatuation with the activity.

The question of why anyone paints is often accompanied by the calamitous idea that the driving force behind it has to be hard work. This is a position that I reject categorically. And yet if painting is a gratifying experience and not hard work, it doesn’t mean that painting takes place in a state of idleness or that it doesn’t sometimes lead to extreme fatigue. Painting is not a matter of pretending. For someone like me who is so pas- sionate and enthusiastic about it, it requires a lot of dedicated persistence. The act of painting raises doubts and questions. Moreover, what gives spice to the adventure is regularly putting yourself in dangerous positions, hesitating and groping around until, hopefully, you are satisfied with the result. Which is never a foregone conclusion. The pleasure of painting cannot achieve its unassailable fullness or soar irresistibly to the heights without complete freedom, which is the absolute condition for it to thrive. Pleasure and freedom are like those birds of the Psittacidae family said to be inseparable. Pleasure and freedom resolutely turn their back on any kind of restriction, any form of fetter or constraint, and on the observance of any ill-foun- ded or dictatorial rule. The only constraints – although I don’t consider them as such – might be the dimensions, the formats of the supports used. But if necessary, I increase the surface area by adding extensions, as and when they are needed.

“Let us reject tedious work. It goes against human nature, against the cosmic rhythms, it goes against man himself, to take trouble where none is needed. [...] Tedious work is inhuman and repugnant, every work which shows signs of it is ugly. It is pleasure and ease, without harshness and constraint, which create grace in every human gesture.”1 No one could put it better than Dubuffet.

Bernard Pruvost – tr. Jeremy Harrison

1. Jean Dubuffet, Notes for the Well-Lettered, Paris, 1967.

Shorten

Read more

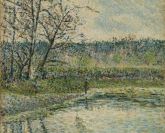

Antoine Chintreuil

(1814 - 1873)

Antoine Chintreuil

(1814 - 1873)

Pierre Révoil

(Lyon 1776 – 1842)

Pierre Révoil

(Lyon 1776 – 1842)

Jacques-Louis David

(Paris, 1748 – Bruxelles, 1825)

Jacques-Louis David

(Paris, 1748 – Bruxelles, 1825)

Jean-Baptiste REGNAULT, Baron

Paris, 1754 – Id., 1829

Jean-Baptiste REGNAULT, Baron

Paris, 1754 – Id., 1829

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 – id., 1657)

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 – id., 1657)

Louis Adrien Masreliez

(Paris, 1748 – Stockholm, 1810)

Louis Adrien Masreliez

(Paris, 1748 – Stockholm, 1810)

Antoine Berjon

(Lyon, 1754 – id., 1838)

Antoine Berjon

(Lyon, 1754 – id., 1838)

Geer van Velde

(Lisse, 1898 – Cachan, 1977)

Geer van Velde

(Lisse, 1898 – Cachan, 1977)

Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld

(Carpentras, 1758 - Montmorency, 1846)

Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld

(Carpentras, 1758 - Montmorency, 1846)

Philippe-Auguste Hennequin

(Lyon, 1762 – Leuze, près de Tournai, 1833)

Philippe-Auguste Hennequin

(Lyon, 1762 – Leuze, près de Tournai, 1833)

Julien Adolphe Duvocelle

(Lille, 1873 – Corbeil-Essonnes, 1961)

Julien Adolphe Duvocelle

(Lille, 1873 – Corbeil-Essonnes, 1961)

François-Joseph Navez

(Charleroi, 1787 – Bruxelles, 1869)

François-Joseph Navez

(Charleroi, 1787 – Bruxelles, 1869)

Philippe-Auguste Immenraet

(Anvers, 1627 – id., 1679)

Philippe-Auguste Immenraet

(Anvers, 1627 – id., 1679)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonnard

(Grasse, 1780 – Paris, 1850)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonnard

(Grasse, 1780 – Paris, 1850)

Jeanne-Elisabeth Chaudet

(Paris, 1767 - id., 1832)

Jeanne-Elisabeth Chaudet

(Paris, 1767 - id., 1832)

Charles Barthélemy Jean Durupt

(Paris, 1804 - id., 1838)

Charles Barthélemy Jean Durupt

(Paris, 1804 - id., 1838)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonard

(Grasse, 1780 - Paris, 1850)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonard

(Grasse, 1780 - Paris, 1850)

Jean-Antoine Laurent

(Baccarat, 1736 - Epinal, 1832)

Jean-Antoine Laurent

(Baccarat, 1736 - Epinal, 1832)

Rafael Tejeo Diaz, dit Tejeo (ou Tegeo)

(Caravaca de la Cruz, Murcie, 1798 - Madrid, 1856)

Rafael Tejeo Diaz, dit Tejeo (ou Tegeo)

(Caravaca de la Cruz, Murcie, 1798 - Madrid, 1856)

Eric Forbes-Robertson

(Londres, 1865 – id., 1935)

Eric Forbes-Robertson

(Londres, 1865 – id., 1935)

Victor Orsel

(Oullins, 1795 – Paris, 1850)

Victor Orsel

(Oullins, 1795 – Paris, 1850)

François-Xavier Fabre

(Montpellier, 1766 – id., 1837)

François-Xavier Fabre

(Montpellier, 1766 – id., 1837)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 – Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, 1986)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 – Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, 1986)

Merry-Joseph Blondel

(Paris, 1781 – id., 1853)

Merry-Joseph Blondel

(Paris, 1781 – id., 1853)

Jean-Jacques Forty

(Marseille, 1743 – Aix-en-Provence, 1801)

Jean-Jacques Forty

(Marseille, 1743 – Aix-en-Provence, 1801)

François Eisen

(1695, Bruxelles – 1778, Paris)

François Eisen

(1695, Bruxelles – 1778, Paris)

Clément Jayet

(Langres, 1731 - Lyon, 1804)

Clément Jayet

(Langres, 1731 - Lyon, 1804)

Cornelis De Beer

(Utrecht, 1591 - Madrid, 1651)

Cornelis De Beer

(Utrecht, 1591 - Madrid, 1651)

Adam De Coster

(Malines, c. 1586, Antwerp, 1643)

Adam De Coster

(Malines, c. 1586, Antwerp, 1643)

Giovanni David

(Gabella Ligure, 1749 - Gênes, 1790)

Giovanni David

(Gabella Ligure, 1749 - Gênes, 1790)

Antoine Dubost

(Lyon, 769 - Paris, 1825)

Antoine Dubost

(Lyon, 769 - Paris, 1825)

Joseph Denis Odevaere

(Bruges, 1775 - Bruxelles, 1830)

Joseph Denis Odevaere

(Bruges, 1775 - Bruxelles, 1830)

Henri-Joseph Forestier

(Puerto Hincado, Santo Domingo, 1787 – Paris, 1872)

Henri-Joseph Forestier

(Puerto Hincado, Santo Domingo, 1787 – Paris, 1872)

Luca Giordano

(Naples, 1634 - id., 1705)

Luca Giordano

(Naples, 1634 - id., 1705)

Emile Didier

(Lyon, 1890 - id., 1965)

Emile Didier

(Lyon, 1890 - id., 1965)

Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret

(Bordeaux, 1782 - Paris, 1863)

Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret

(Bordeaux, 1782 - Paris, 1863)

André Bouys

(Hyères, 1656 - Paris, 1740)

André Bouys

(Hyères, 1656 - Paris, 1740)

Jacques-François Delyen

(Gand, 1684 - Paris, 1761)

Jacques-François Delyen

(Gand, 1684 - Paris, 1761)

-165x133.jpg) Jean-Jacques de Boissieu

(Lyon, 1736 - id., 1810)

Jean-Jacques de Boissieu

(Lyon, 1736 - id., 1810)

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux

(1827 - 1875)

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux

(1827 - 1875)

James Ensor

(Ostende, 1860 - id., 1949)

James Ensor

(Ostende, 1860 - id., 1949)

Jean Cocteau

(Maisons-Laffitte, 1889 - Milly-la-Forêt, 1963)

Jean Cocteau

(Maisons-Laffitte, 1889 - Milly-la-Forêt, 1963)

Antoine Demilly

(Mâcon, 1892 – Lyon, 1964)

Antoine Demilly

(Mâcon, 1892 – Lyon, 1964)

Charles Dukes

actif à Londres entre 1829 et 1865

Charles Dukes

actif à Londres entre 1829 et 1865

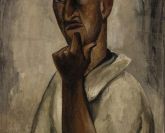

Crikor GARABÉTIAN

Bucarest, 1908 – Lyon, 1993

Crikor GARABÉTIAN

Bucarest, 1908 – Lyon, 1993

Pierre Tal-Coat [Pierre Jacob]

(Clohars-Carnoët, 1905 – Saint-Pierre-de-Bailleul, 1985)

Pierre Tal-Coat [Pierre Jacob]

(Clohars-Carnoët, 1905 – Saint-Pierre-de-Bailleul, 1985)

Pierre Molinier

(Agen, 1900 - Bordeaux, 1976)

Pierre Molinier

(Agen, 1900 - Bordeaux, 1976)

Patrice Giorda

né en 1952

Patrice Giorda

né en 1952

Frédéric Benrath

(Lyon, 1930 - Paris, 2007)

Frédéric Benrath

(Lyon, 1930 - Paris, 2007)

Félix Labisse

(Marchiennes (Nord), 1908 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1982)

Félix Labisse

(Marchiennes (Nord), 1908 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1982)

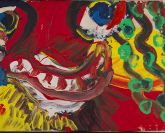

Bengt Lindström

(1925 - 2008)

Bengt Lindström

(1925 - 2008)

Bengt Lindström

(1925 - 2008)

Bengt Lindström

(1925 - 2008)

Jean-Batpiste Oudry

Paris, 1686 – Beauvais, 1755)

Jean-Batpiste Oudry

Paris, 1686 – Beauvais, 1755)

Albert Marquet

(Bordeaux, 1875 - Paris, 1947)

Albert Marquet

(Bordeaux, 1875 - Paris, 1947)

Balthasar K?OSSOWSKI DE ROLA, dit BALTHUS

(Paris, 1908 – Rossinière, 2001)

Balthasar K?OSSOWSKI DE ROLA, dit BALTHUS

(Paris, 1908 – Rossinière, 2001)

Gioavni Paolo Panini

(Plaisance, 1691 – Rome, 1765)

Gioavni Paolo Panini

(Plaisance, 1691 – Rome, 1765)

Alberto Savinio

(Athènes, 1891 - Rome, 1952)

Alberto Savinio

(Athènes, 1891 - Rome, 1952)

Oskar Bergman

(Stockholm, 1879 - id., 1963)

Oskar Bergman

(Stockholm, 1879 - id., 1963)

Léon Pourtau

(Bordeaux, 1868 - mort en mer, 1898)

Léon Pourtau

(Bordeaux, 1868 - mort en mer, 1898)

Jean-Baptiste Chatigny

(Lyon, 1834 - id., 1886)

Jean-Baptiste Chatigny

(Lyon, 1834 - id., 1886)

Adolphe Appian

(Lyon, 1814 – id., 1898)

Adolphe Appian

(Lyon, 1814 – id., 1898)

Paul Huet

(Paris, 1803 - id., 1869)

Paul Huet

(Paris, 1803 - id., 1869)

Fabius, dit Fabien Van Risamburgh

(Lyon, 1794 – Saint-Gengoux-le-National, Saône-et-Loire, 1866)

Fabius, dit Fabien Van Risamburgh

(Lyon, 1794 – Saint-Gengoux-le-National, Saône-et-Loire, 1866)

Jacques-Augustin Pajou

(Paris, 1766 b- id., 1828)

Jacques-Augustin Pajou

(Paris, 1766 b- id., 1828)

Louis Lafitte

(Paris, 1770 – id., 1828)

Louis Lafitte

(Paris, 1770 – id., 1828)

Louis Bélanger

(Paris, 1756 - Stockholm, 1816)

Louis Bélanger

(Paris, 1756 - Stockholm, 1816)

Claude Joseph Vernet

(Avignon, 1714 - Paris, 1799)

Claude Joseph Vernet

(Avignon, 1714 - Paris, 1799)

Joseph Wright of Derby

(Derby, 1734 – id., 1797)

Joseph Wright of Derby

(Derby, 1734 – id., 1797)

Claude-Joseph Vernet

(Avignon, 1714 – Paris, 1789)

Claude-Joseph Vernet

(Avignon, 1714 – Paris, 1789)

Philippe-Auguste Hennequin

(Luo, 1762 - Leuze, near Tournai, 1833)

Philippe-Auguste Hennequin

(Luo, 1762 - Leuze, near Tournai, 1833)

Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, known as Balthus

(Paris, 1908 - Rossinière, 2001)

Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, known as Balthus

(Paris, 1908 - Rossinière, 2001)

Jean-Baptiste Oudry

(Paris, 1686 - Beauvais, 1755)

Jean-Baptiste Oudry

(Paris, 1686 - Beauvais, 1755)

Jean Daret

(Brussels, 1614 - Paris, 1668)

Jean Daret

(Brussels, 1614 - Paris, 1668)

Jean Dubuffet

(Le Havre, 1901 - Paris, 1985)

Jean Dubuffet

(Le Havre, 1901 - Paris, 1985)

Fabius, known as Fabien van Risamburgh

(Lyon, 1794 - Saint-Gengoux-le-National, Saône-et-Loire, 1866)

Fabius, known as Fabien van Risamburgh

(Lyon, 1794 - Saint-Gengoux-le-National, Saône-et-Loire, 1866)

Gustave Moreau

(Paris, 1826 – id., 1898)

Gustave Moreau

(Paris, 1826 – id., 1898)

Rhin supérieur, entourage de Martin Schongauer ?

Rhin supérieur, entourage de Martin Schongauer ?

Giovanni Battista Castello, dit Il Bergamasco

(Crema, vers 1526 – El Escorial, 1569)

Giovanni Battista Castello, dit Il Bergamasco

(Crema, vers 1526 – El Escorial, 1569)

Giuseppe Antonio Pianca

Agnona, 1703 – Milano, 1762)

Giuseppe Antonio Pianca

Agnona, 1703 – Milano, 1762)

Pierre TAL-COAT (Pierre JACOB)

(Clohars-Carnoët, 1905 – Saint-Pierre-de-Bailleul, 1985)

Pierre TAL-COAT (Pierre JACOB)

(Clohars-Carnoët, 1905 – Saint-Pierre-de-Bailleul, 1985)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 - Rochetaillées-sur-Saône, 1986)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 - Rochetaillées-sur-Saône, 1986)

Camille Rogier

(1810-1896)

Camille Rogier

(1810-1896)

Paris BORDONE

(Trévise, 1500 - Venise, 1571)

Paris BORDONE

(Trévise, 1500 - Venise, 1571)

-165x133.jpg) Maître de l'Incrédulitgé de saint Thomas (Jean Ducamps ?)

Actif à Rome de la fin des années 1920 à 1637

Maître de l'Incrédulitgé de saint Thomas (Jean Ducamps ?)

Actif à Rome de la fin des années 1920 à 1637

-165x133.jpg) Claude Nattiez

(actif à Rome entre 1641 et 1660)

Claude Nattiez

(actif à Rome entre 1641 et 1660)

Simon Demasso

(Lyon, 1658 - id., 1738

Simon Demasso

(Lyon, 1658 - id., 1738

Charles-François Hutin

(Paris, 1715-Dresde, 1776)

Charles-François Hutin

(Paris, 1715-Dresde, 1776)

Louis Adrien MASRELIEZ

(Paris, 1748 - Stockholm, 1810)

Louis Adrien MASRELIEZ

(Paris, 1748 - Stockholm, 1810)

Pierre Peyron

(Aix-en-Provence, 1744 - Paris, 1814)

Pierre Peyron

(Aix-en-Provence, 1744 - Paris, 1814)

Philippe DEREUX

(Lyon, 1918 - Villeurbanne, 2001)

Philippe DEREUX

(Lyon, 1918 - Villeurbanne, 2001)

Robert MALAVAL

(Nice, 1937 - Paris, 1980)

Robert MALAVAL

(Nice, 1937 - Paris, 1980)

-165x133.jpg) Bernard REQUICHOT

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, 1929 - Paris, 1961)

Bernard REQUICHOT

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, 1929 - Paris, 1961)

Bernard REQUICHOT

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, Sarthe, 1929 – Paris, 1961)

Bernard REQUICHOT

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, Sarthe, 1929 – Paris, 1961)

Oskar Bergman

(Stockholm, 1879 – id., 1963)

Oskar Bergman

(Stockholm, 1879 – id., 1963)

Mélanie DELATTRE-VOGT

(Valenciennes, 1984)

Mélanie DELATTRE-VOGT

(Valenciennes, 1984)

Helmer Osslund

(Tuna, 1866 – Stockholm, 1938)

Helmer Osslund

(Tuna, 1866 – Stockholm, 1938)

Marcel ROUX

(Bessenay, 1878 – Chartres, 1922)

Marcel ROUX

(Bessenay, 1878 – Chartres, 1922)

Jules-Elie DELAUNAY

(Nantes, 1828 – Paris, 1891)

Jules-Elie DELAUNAY

(Nantes, 1828 – Paris, 1891)

Ernest Antoine Hebert

(Grenoble, 1817 – La Tronche, 1908)

Ernest Antoine Hebert

(Grenoble, 1817 – La Tronche, 1908)

Harald Jerichau

(Copenhague, 1851 – Rome, 1878)

Harald Jerichau

(Copenhague, 1851 – Rome, 1878)

Eugène Roger

(Sens, 1807 – Paris, 1840)

Eugène Roger

(Sens, 1807 – Paris, 1840)

-165x133.jpg) François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

-165x133.jpg) Alberto GIRONELLA

(Mexico, 1929 – Valle de Bravo (Mexique), 1999)

Alberto GIRONELLA

(Mexico, 1929 – Valle de Bravo (Mexique), 1999)

Nicolas-Antoine Taunay

(Paris, 1755 – id., 1830)

Nicolas-Antoine Taunay

(Paris, 1755 – id., 1830)

-165x133.jpg) François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

-165x133.jpg) Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld

(Carpentras, 1758 – Montmorency, 1846)

Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld

(Carpentras, 1758 – Montmorency, 1846)

-165x133.jpg) Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 – Paris, 1657)

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 – Paris, 1657)

Paris BORDONE

(Treviso, 1500 – Venice, 1571)

Paris BORDONE

(Treviso, 1500 – Venice, 1571)

-165x133.jpg) Raoul UBAC

(Malmedy or Cologne, 1910 – Dieudonné, 1985)

Raoul UBAC

(Malmedy or Cologne, 1910 – Dieudonné, 1985)

-165x133.jpg) Robert Malaval

(Nice, 1937 – Paris, 1980)

Robert Malaval

(Nice, 1937 – Paris, 1980)

Pierre Peyron

(Aix-en-Provence, 1744 – Paris, 1814)

Pierre Peyron

(Aix-en-Provence, 1744 – Paris, 1814)

Jules-Elie Delaunay

(Nantes, 1828 – Paris, 1891)

Jules-Elie Delaunay

(Nantes, 1828 – Paris, 1891)

Marcel Roux

(Bessenay, 1878 – Chartres, 1922)

Marcel Roux

(Bessenay, 1878 – Chartres, 1922)

-165x133.jpg) Alberto Gironella

(Mexico, 1929 – Valle de Bravo (Mexico), 1999) 32. El entierro de Zapata y ostros enterramientos [Funeral of Zapata and Other Burials], Elas de Oro II, 1972 A tribute to Zapata Alberto Gironella (1929-1999) had his first exhibition in 1952 in a gallery in

Alberto Gironella

(Mexico, 1929 – Valle de Bravo (Mexico), 1999) 32. El entierro de Zapata y ostros enterramientos [Funeral of Zapata and Other Burials], Elas de Oro II, 1972 A tribute to Zapata Alberto Gironella (1929-1999) had his first exhibition in 1952 in a gallery in

-165x133.jpg) Thomas Blanchet

(Paris, 1614 – Lyon, 1689)

Thomas Blanchet

(Paris, 1614 – Lyon, 1689)

Valentin Lefèvre

(Bruxelles, 1637 – Venise, 1677)

Valentin Lefèvre

(Bruxelles, 1637 – Venise, 1677)

Laurent Pécheux

Lyon, 1729 – Turin, 1821

Laurent Pécheux

Lyon, 1729 – Turin, 1821

Jean-Baptiste Deshays

(Rouen, 1729 – Paris, 1765)

Jean-Baptiste Deshays

(Rouen, 1729 – Paris, 1765)

Joseph François Ducq

(Ledeghem, 1762 – Bruges, 1829)

Joseph François Ducq

(Ledeghem, 1762 – Bruges, 1829)

Holger Drachmann

(Copenhague, 1846 – Hornbaek, 1908)

Holger Drachmann

(Copenhague, 1846 – Hornbaek, 1908)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 – id., 1947)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 – id., 1947)

Arthur George Walker

(Londres, 1861 – id., 1939)

Arthur George Walker

(Londres, 1861 – id., 1939)

Claude-Marie DUBUFE

(Paris, 1790 – Celle-Saint-Cloud, 1864)

Claude-Marie DUBUFE

(Paris, 1790 – Celle-Saint-Cloud, 1864)

-165x133.jpg) Nicolas Bertin

(Paris, 1668 – id., 1736)

Nicolas Bertin

(Paris, 1668 – id., 1736)

Vincent Bioulès

(Montpellier, 1938)

Vincent Bioulès

(Montpellier, 1938)

Paul Borel

(Lyon, 1828 – id., 1913)

Paul Borel

(Lyon, 1828 – id., 1913)

Giuseppe Cades

(Rome, 1750 – id., 1799)

Giuseppe Cades

(Rome, 1750 – id., 1799)

Andreas Joseph Chandelle

(Francfort, 1743-Id., 1820)

Andreas Joseph Chandelle

(Francfort, 1743-Id., 1820)

Émilie Charmy

(Saint Etienne, 1978 – Crosne, 1974)

Émilie Charmy

(Saint Etienne, 1978 – Crosne, 1974)

Michel Dorigny

(Saint-Quentin, 1616 – Paris, 1665)

Michel Dorigny

(Saint-Quentin, 1616 – Paris, 1665)

-165x133.jpg) Gustaf Fjaestad

(Stockholm, 1868 – Arvika, 1948)

Gustaf Fjaestad

(Stockholm, 1868 – Arvika, 1948)

François Gérard

(Rome, 1770 – Paris, 1837)

François Gérard

(Rome, 1770 – Paris, 1837)

Nicolas Henri Jeaurat de Bertry

(Paris, 1728 – id., vers 1796)

Nicolas Henri Jeaurat de Bertry

(Paris, 1728 – id., vers 1796)

Paul Jourdy

(Dijon, 1805 – Paris, 1856)

Paul Jourdy

(Dijon, 1805 – Paris, 1856)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 – Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, 1986)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 – Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, 1986)

Bernard Réquichot

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, Sarthe, 1929 – Paris, 1961)

Bernard Réquichot

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, Sarthe, 1929 – Paris, 1961)

Henri Michaux

(1899, Namur – 1984, Paris)

Henri Michaux

(1899, Namur – 1984, Paris)

Mario Alejandro Yllanes

(Oruro, 1913 – 1946 ?)

Mario Alejandro Yllanes

(Oruro, 1913 – 1946 ?)

Joseph-Benoît Suvée

(Bruges, 1743 – Rome, 1807)

Joseph-Benoît Suvée

(Bruges, 1743 – Rome, 1807)

-165x133.jpg) Joseph-Benoît Suvée

(Bruges, 1743 – Rome, 1807)

Joseph-Benoît Suvée

(Bruges, 1743 – Rome, 1807)

James Pradier

(Genève, 1790 – Bougival, 1852)

James Pradier

(Genève, 1790 – Bougival, 1852)

Pierre Révoil

(Lyon, 1776 – Paris, 1842)

Pierre Révoil

(Lyon, 1776 – Paris, 1842)

Jean-Baptiste Chatigny

(Lyon, 1834 – id., 1886)

Jean-Baptiste Chatigny

(Lyon, 1834 – id., 1886)

Louis Jean-François LAGRENEE, dit l’Aîné

(Paris, 1725 – Paris, 1805)

Louis Jean-François LAGRENEE, dit l’Aîné

(Paris, 1725 – Paris, 1805)

Michel-François Dandré-Bardon

Aix-en-Provence, 1700 – Paris, 1783

Michel-François Dandré-Bardon

Aix-en-Provence, 1700 – Paris, 1783

Hans Ditlev Martens

(Kiel, 1795 – Id., 1864)

Hans Ditlev Martens

(Kiel, 1795 – Id., 1864)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 – Id., 1947)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 – Id., 1947)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

Jeanne Bardey

(Lyon, 1872 - id., 1954)

Jeanne Bardey

(Lyon, 1872 - id., 1954)

André Utter

(Paris, 1886 - id., 1948)

André Utter

(Paris, 1886 - id., 1948)

Élisabeth Sonrel

(Tours, 1874 - Sceaux, 1953)

Élisabeth Sonrel

(Tours, 1874 - Sceaux, 1953)

Bernard Pruvost

(Alger, 1952)

Bernard Pruvost

(Alger, 1952)

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 - Paris, 1657)

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 - Paris, 1657)

Louis Cretey

(Lyon, before 1638 - Rome (?), after 1702)

Louis Cretey

(Lyon, before 1638 - Rome (?), after 1702)

Michel-François Dandré-Bardon

(Aix-en-Provence, 1700 - Paris, 1783)

Michel-François Dandré-Bardon

(Aix-en-Provence, 1700 - Paris, 1783)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 - Id., 1849)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 - Id., 1849)

Hans Ditlev Martens

(Kiel, 1795 - Kiel, 1864)

Hans Ditlev Martens

(Kiel, 1795 - Kiel, 1864)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 - Id., 1947)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 - Id., 1947)

Jeanne Bardey

(Lyon, 1872 - id., 1954)

Jeanne Bardey

(Lyon, 1872 - id., 1954)

André Utter

(Paris, 1886 – Id., 1948)

André Utter

(Paris, 1886 – Id., 1948)

Élisabeth Sonrel

Élisabeth Sonrel

Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg

(Sundeved, 1783 - Copenhague, 1853)

Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg

(Sundeved, 1783 - Copenhague, 1853)

Jean-François Forty (actif à Paris, 1775–90)

Jean-François Forty (actif à Paris, 1775–90)

Thomas Blanchet

(Paris, 1614 - Lyon, 1689)

Thomas Blanchet

(Paris, 1614 - Lyon, 1689)

Claude Nattiez

(actif à Rome entre 1641 et 1660)

Claude Nattiez

(actif à Rome entre 1641 et 1660)

Jean Charles Frontier

(Paris, 1701 – Lyon, 1763)

Jean Charles Frontier

(Paris, 1701 – Lyon, 1763)

Pierre Nicolas Legrand de Sérant

(Pont-l’Évêque, 1758 – Berne, 1829)

Pierre Nicolas Legrand de Sérant

(Pont-l’Évêque, 1758 – Berne, 1829)

Jean-Baptiste Isabey

(Nancy, 1767 – Paris, 1855)

Jean-Baptiste Isabey

(Nancy, 1767 – Paris, 1855)