Read more

Jean Daret, who was born in Brussels in 1614, began his apprenticeship with Antoine van Opstal (1592-1653) a painter at the court of the Archdukes, at the age of 11. By 1633, he was in Paris where he is documented at wedding of his first cousin Pierre Daret (1605-1678), a printmaker who engraved after paintings by the major artists of his time such as Simon Vouet (1590-1649) and Jacques Blanchard (1600-1638). Jean left the French capital in early 1634, probably to go to Italy.

He is next to be found in Aix-en-Provence about 1636, where he married the daughter of a member of the local bourgeoisie and remained for about thirty years. There he was involved in the decoration of churches and convents in the town (Saint Dominic and Saint Catherine, 1643, Aix-en-Provence, Church of the Magdalen) and surrounding region (Miracle of Soriano, 1649, Grasse, Musée d’Art et d’Histoire). He worked mostly for private clients, members of the local nobility who requested paintings for their private chapels (Crucifixion, 1640, Aix-en-Provence, Saint-Sauveur cathedral), mythological subjects (Asclepius Reviving Hippolytus, 1636, Marseille, Musée des Beaux-Arts), genre scenes (the Guitar Player, 1636, Aix-en-Provence, Musée Granet) and private devotional subjects (Education of the Virgin, 1655, private collection). The trompe-l’oeil decoration in the staircase of the hotel de Chateaurenard is the only evidence of his work as a painter of decorations to remain in situ. Louis XIV admired it while he was staying in Aix in 1660.1 This work has earned Daret a reputation as a painter of decorations.

In 1659, Daret decided to go to Paris where he was involved in the decoration work at the château de Vincennes (destroyed) and made a number of portraits (Nicolas Sanson, lost but known from the print by Jan Edelinck). He was admitted as a member of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture on 15 September 1663 and returned to Aix the following year. He continued to work for local patrons such as Pierre Maurel de Pontevès (1601-1672), who commissioned a number of decorations for his chateau at Pontevès (Var). He was painting the ceiling for the chapel of the Pénitents Blancs de l’Observance (destroyed, preparatory drawing, Rouen, Musée des Beaux-Arts) when he died in 1668.

Daret’s work as a painter of religious subjects is well known today thanks to the many documents that record them. The surviving paintings show a particular interest in the use of colour, the realistic treatment of details and skilful foreshortening. But it is in his profane works – now less common and less well documented – that Daret seems to have at his most creative. The compositions are innovative, the settings are carefully constructed and the colours subtle. The painting catalogued here shows all of these qualities.

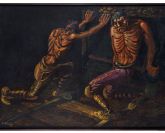

The oval composition has been painted on a rectangular canvas, intended to be set into wainscoting. It is a battle scene with figures piled up in the foreground, a view towards a distant town in flames on the right. The poses of the soldiers follow the oval shape, echoing it within the painting. Daret’s skills with colour can be seen here. He has used a shimmering range: pink, blue, red, orange and violet that oppose the muter shades of olive green, brown and grey of the horses, the armour and some clothing. This way of building up the composition

using colour is typical of Daret and can be found in his Conversion of St. Paul (see ill. I), in which he has similarly arranged his composition around areas of strong colour using red, blue and violet.

The clothing and bodies of the warriors are painted freely and with confidence describing the muscles visible under the cloth. Their heavy-set shapes, their round, pale faces, the subtle shadows giving them volume are all typical of Daret and appear in the Conversion of St. Paul. This composition is made dynamic by the movements in opposite directions of St. Paul and his companions, a type of opposition also visible in our painting. These similarities in addition to the artist’s obvious confidence in creating this battle scene, the varied touches of paint and the different parts of the figures: broad and free on the drapery, more precise and delicate in the decoration of the arms, helmets and swords, indicate that our Battle Scene like the Conversion of St. Paul, should be dated to the mid-1640s. It would be risky to attempt further identification of this scene. It is set against a city in flames, which has no recognizable elements. In addition, the soldiers wearing antique armour do not have any recognizable attributes.

This absence is doubtless due to the fact that our painting was part of a series of compositions illustrating a pastoral tale such as Aethiopica by Heliodorus of Emesa or an ancient text such as Livy’s Histories. However, it is possible to exclude the Gerusalemme liberate by Tasso as a source, as painters usually identified the Muslim soldiers of the story with turbans, which are not visible in our composition.

This unpublished Battle Scene is an important example of Daret’s talents as a painter of decorative compositions. Although his Diana and Callisto (1642, Marseille Musée des Beaux-Arts), intended for a ceiling, is already known, its condition has suffered considerably. The excellent condition of our painting is exceptional and allows us to understand the richness of Daret’s manner as a painter of narrative scenes. Jane MacAvock

1. Jane MacAvock, “La fortune de la peinture religieuse en Provence au XVIIe siècle: copies et pastiches d’oeuvres de Nicolas Mignard et de Jean Daret” Regards sur les tableaux religieux: XVIIème – XIXème siècle, Arles, 2013, p. 60.

2. Pierre-Joseph d’Haitze, Les curiositez les plus remarquables de la ville d’Aix, A Aix, chez Charles David, 1679, p. 60.

3. Recueil des principaux évènemens de la confrérie des Frères Pénitens Blancs près l’Observance de la ville d’Aix, Aix-en-Provence, Bibliothèque Paul-Arbaud, about 1721, Ms. MF 197. Not paginated,

4. The story was illustrated by Nicolas Mignard in Avignon in the mid-1630s, see A. Schnapper, Nicolas Mignard d’Avignon, Avignon, 1979, no. 7.

5. We thank Mr M. Alexis Merle du Bourg for his lightings on this point.

Shorten

Read more

Antoine Chintreuil

(1814 - 1873)

Antoine Chintreuil

(1814 - 1873)

Pierre Révoil

(Lyon 1776 – 1842)

Pierre Révoil

(Lyon 1776 – 1842)

Jacques-Louis David

(Paris, 1748 – Bruxelles, 1825)

Jacques-Louis David

(Paris, 1748 – Bruxelles, 1825)

Jean-Baptiste REGNAULT, Baron

Paris, 1754 – Id., 1829

Jean-Baptiste REGNAULT, Baron

Paris, 1754 – Id., 1829

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 – id., 1657)

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 – id., 1657)

Louis Adrien Masreliez

(Paris, 1748 – Stockholm, 1810)

Louis Adrien Masreliez

(Paris, 1748 – Stockholm, 1810)

Antoine Berjon

(Lyon, 1754 – id., 1838)

Antoine Berjon

(Lyon, 1754 – id., 1838)

Geer van Velde

(Lisse, 1898 – Cachan, 1977)

Geer van Velde

(Lisse, 1898 – Cachan, 1977)

Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld

(Carpentras, 1758 - Montmorency, 1846)

Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld

(Carpentras, 1758 - Montmorency, 1846)

Philippe-Auguste Hennequin

(Lyon, 1762 – Leuze, près de Tournai, 1833)

Philippe-Auguste Hennequin

(Lyon, 1762 – Leuze, près de Tournai, 1833)

Julien Adolphe Duvocelle

(Lille, 1873 – Corbeil-Essonnes, 1961)

Julien Adolphe Duvocelle

(Lille, 1873 – Corbeil-Essonnes, 1961)

François-Joseph Navez

(Charleroi, 1787 – Bruxelles, 1869)

François-Joseph Navez

(Charleroi, 1787 – Bruxelles, 1869)

Philippe-Auguste Immenraet

(Anvers, 1627 – id., 1679)

Philippe-Auguste Immenraet

(Anvers, 1627 – id., 1679)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonnard

(Grasse, 1780 – Paris, 1850)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonnard

(Grasse, 1780 – Paris, 1850)

Jeanne-Elisabeth Chaudet

(Paris, 1767 - id., 1832)

Jeanne-Elisabeth Chaudet

(Paris, 1767 - id., 1832)

Charles Barthélemy Jean Durupt

(Paris, 1804 - id., 1838)

Charles Barthélemy Jean Durupt

(Paris, 1804 - id., 1838)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonard

(Grasse, 1780 - Paris, 1850)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonard

(Grasse, 1780 - Paris, 1850)

Jean-Antoine Laurent

(Baccarat, 1736 - Epinal, 1832)

Jean-Antoine Laurent

(Baccarat, 1736 - Epinal, 1832)

Rafael Tejeo Diaz, dit Tejeo (ou Tegeo)

(Caravaca de la Cruz, Murcie, 1798 - Madrid, 1856)

Rafael Tejeo Diaz, dit Tejeo (ou Tegeo)

(Caravaca de la Cruz, Murcie, 1798 - Madrid, 1856)

Eric Forbes-Robertson

(Londres, 1865 – id., 1935)

Eric Forbes-Robertson

(Londres, 1865 – id., 1935)

Victor Orsel

(Oullins, 1795 – Paris, 1850)

Victor Orsel

(Oullins, 1795 – Paris, 1850)

François-Xavier Fabre

(Montpellier, 1766 – id., 1837)

François-Xavier Fabre

(Montpellier, 1766 – id., 1837)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 – Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, 1986)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 – Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, 1986)

Merry-Joseph Blondel

(Paris, 1781 – id., 1853)

Merry-Joseph Blondel

(Paris, 1781 – id., 1853)

Jean-Jacques Forty

(Marseille, 1743 – Aix-en-Provence, 1801)

Jean-Jacques Forty

(Marseille, 1743 – Aix-en-Provence, 1801)

François Eisen

(1695, Bruxelles – 1778, Paris)

François Eisen

(1695, Bruxelles – 1778, Paris)

Clément Jayet

(Langres, 1731 - Lyon, 1804)

Clément Jayet

(Langres, 1731 - Lyon, 1804)

Cornelis De Beer

(Utrecht, 1591 - Madrid, 1651)

Cornelis De Beer

(Utrecht, 1591 - Madrid, 1651)

Adam De Coster

(Malines, c. 1586, Antwerp, 1643)

Adam De Coster

(Malines, c. 1586, Antwerp, 1643)

Giovanni David

(Gabella Ligure, 1749 - Gênes, 1790)

Giovanni David

(Gabella Ligure, 1749 - Gênes, 1790)

Antoine Dubost

(Lyon, 769 - Paris, 1825)

Antoine Dubost

(Lyon, 769 - Paris, 1825)

Joseph Denis Odevaere

(Bruges, 1775 - Bruxelles, 1830)

Joseph Denis Odevaere

(Bruges, 1775 - Bruxelles, 1830)

Henri-Joseph Forestier

(Puerto Hincado, Santo Domingo, 1787 – Paris, 1872)

Henri-Joseph Forestier

(Puerto Hincado, Santo Domingo, 1787 – Paris, 1872)

Luca Giordano

(Naples, 1634 - id., 1705)

Luca Giordano

(Naples, 1634 - id., 1705)

Emile Didier

(Lyon, 1890 - id., 1965)

Emile Didier

(Lyon, 1890 - id., 1965)

Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret

(Bordeaux, 1782 - Paris, 1863)

Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret

(Bordeaux, 1782 - Paris, 1863)

André Bouys

(Hyères, 1656 - Paris, 1740)

André Bouys

(Hyères, 1656 - Paris, 1740)

Jacques-François Delyen

(Gand, 1684 - Paris, 1761)

Jacques-François Delyen

(Gand, 1684 - Paris, 1761)

-165x133.jpg) Jean-Jacques de Boissieu

(Lyon, 1736 - id., 1810)

Jean-Jacques de Boissieu

(Lyon, 1736 - id., 1810)

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux

(1827 - 1875)

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux

(1827 - 1875)

James Ensor

(Ostende, 1860 - id., 1949)

James Ensor

(Ostende, 1860 - id., 1949)

Jean Cocteau

(Maisons-Laffitte, 1889 - Milly-la-Forêt, 1963)

Jean Cocteau

(Maisons-Laffitte, 1889 - Milly-la-Forêt, 1963)

Antoine Demilly

(Mâcon, 1892 – Lyon, 1964)

Antoine Demilly

(Mâcon, 1892 – Lyon, 1964)

Charles Dukes

actif à Londres entre 1829 et 1865

Charles Dukes

actif à Londres entre 1829 et 1865

Crikor GARABÉTIAN

Bucarest, 1908 – Lyon, 1993

Crikor GARABÉTIAN

Bucarest, 1908 – Lyon, 1993

Pierre Tal-Coat [Pierre Jacob]

(Clohars-Carnoët, 1905 – Saint-Pierre-de-Bailleul, 1985)

Pierre Tal-Coat [Pierre Jacob]

(Clohars-Carnoët, 1905 – Saint-Pierre-de-Bailleul, 1985)

Pierre Molinier

(Agen, 1900 - Bordeaux, 1976)

Pierre Molinier

(Agen, 1900 - Bordeaux, 1976)

Patrice Giorda

né en 1952

Patrice Giorda

né en 1952

Frédéric Benrath

(Lyon, 1930 - Paris, 2007)

Frédéric Benrath

(Lyon, 1930 - Paris, 2007)

Félix Labisse

(Marchiennes (Nord), 1908 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1982)

Félix Labisse

(Marchiennes (Nord), 1908 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1982)

Bengt Lindström

(1925 - 2008)

Bengt Lindström

(1925 - 2008)

Bengt Lindström

(1925 - 2008)

Bengt Lindström

(1925 - 2008)

Jean-Batpiste Oudry

Paris, 1686 – Beauvais, 1755)

Jean-Batpiste Oudry

Paris, 1686 – Beauvais, 1755)

Albert Marquet

(Bordeaux, 1875 - Paris, 1947)

Albert Marquet

(Bordeaux, 1875 - Paris, 1947)

Balthasar K?OSSOWSKI DE ROLA, dit BALTHUS

(Paris, 1908 – Rossinière, 2001)

Balthasar K?OSSOWSKI DE ROLA, dit BALTHUS

(Paris, 1908 – Rossinière, 2001)

Gioavni Paolo Panini

(Plaisance, 1691 – Rome, 1765)

Gioavni Paolo Panini

(Plaisance, 1691 – Rome, 1765)

Alberto Savinio

(Athènes, 1891 - Rome, 1952)

Alberto Savinio

(Athènes, 1891 - Rome, 1952)

Oskar Bergman

(Stockholm, 1879 - id., 1963)

Oskar Bergman

(Stockholm, 1879 - id., 1963)

Léon Pourtau

(Bordeaux, 1868 - mort en mer, 1898)

Léon Pourtau

(Bordeaux, 1868 - mort en mer, 1898)

Jean-Baptiste Chatigny

(Lyon, 1834 - id., 1886)

Jean-Baptiste Chatigny

(Lyon, 1834 - id., 1886)

Adolphe Appian

(Lyon, 1814 – id., 1898)

Adolphe Appian

(Lyon, 1814 – id., 1898)

Paul Huet

(Paris, 1803 - id., 1869)

Paul Huet

(Paris, 1803 - id., 1869)

Fabius, dit Fabien Van Risamburgh

(Lyon, 1794 – Saint-Gengoux-le-National, Saône-et-Loire, 1866)

Fabius, dit Fabien Van Risamburgh

(Lyon, 1794 – Saint-Gengoux-le-National, Saône-et-Loire, 1866)

Jacques-Augustin Pajou

(Paris, 1766 b- id., 1828)

Jacques-Augustin Pajou

(Paris, 1766 b- id., 1828)

Louis Lafitte

(Paris, 1770 – id., 1828)

Louis Lafitte

(Paris, 1770 – id., 1828)

Louis Bélanger

(Paris, 1756 - Stockholm, 1816)

Louis Bélanger

(Paris, 1756 - Stockholm, 1816)

Claude Joseph Vernet

(Avignon, 1714 - Paris, 1799)

Claude Joseph Vernet

(Avignon, 1714 - Paris, 1799)

Joseph Wright of Derby

(Derby, 1734 – id., 1797)

Joseph Wright of Derby

(Derby, 1734 – id., 1797)

Claude-Joseph Vernet

(Avignon, 1714 – Paris, 1789)

Claude-Joseph Vernet

(Avignon, 1714 – Paris, 1789)

Philippe-Auguste Hennequin

(Luo, 1762 - Leuze, near Tournai, 1833)

Philippe-Auguste Hennequin

(Luo, 1762 - Leuze, near Tournai, 1833)

Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, known as Balthus

(Paris, 1908 - Rossinière, 2001)

Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, known as Balthus

(Paris, 1908 - Rossinière, 2001)

Jean-Baptiste Oudry

(Paris, 1686 - Beauvais, 1755)

Jean-Baptiste Oudry

(Paris, 1686 - Beauvais, 1755)

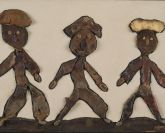

Jean Dubuffet

(Le Havre, 1901 - Paris, 1985)

Jean Dubuffet

(Le Havre, 1901 - Paris, 1985)

Fabius, known as Fabien van Risamburgh

(Lyon, 1794 - Saint-Gengoux-le-National, Saône-et-Loire, 1866)

Fabius, known as Fabien van Risamburgh

(Lyon, 1794 - Saint-Gengoux-le-National, Saône-et-Loire, 1866)

Gustave Moreau

(Paris, 1826 – id., 1898)

Gustave Moreau

(Paris, 1826 – id., 1898)

Rhin supérieur, entourage de Martin Schongauer ?

Rhin supérieur, entourage de Martin Schongauer ?

Giovanni Battista Castello, dit Il Bergamasco

(Crema, vers 1526 – El Escorial, 1569)

Giovanni Battista Castello, dit Il Bergamasco

(Crema, vers 1526 – El Escorial, 1569)

Giuseppe Antonio Pianca

Agnona, 1703 – Milano, 1762)

Giuseppe Antonio Pianca

Agnona, 1703 – Milano, 1762)

Pierre TAL-COAT (Pierre JACOB)

(Clohars-Carnoët, 1905 – Saint-Pierre-de-Bailleul, 1985)

Pierre TAL-COAT (Pierre JACOB)

(Clohars-Carnoët, 1905 – Saint-Pierre-de-Bailleul, 1985)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 - Rochetaillées-sur-Saône, 1986)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 - Rochetaillées-sur-Saône, 1986)

Camille Rogier

(1810-1896)

Camille Rogier

(1810-1896)

Paris BORDONE

(Trévise, 1500 - Venise, 1571)

Paris BORDONE

(Trévise, 1500 - Venise, 1571)

-165x133.jpg) Maître de l'Incrédulitgé de saint Thomas (Jean Ducamps ?)

Actif à Rome de la fin des années 1920 à 1637

Maître de l'Incrédulitgé de saint Thomas (Jean Ducamps ?)

Actif à Rome de la fin des années 1920 à 1637

-165x133.jpg) Claude Nattiez

(actif à Rome entre 1641 et 1660)

Claude Nattiez

(actif à Rome entre 1641 et 1660)

Simon Demasso

(Lyon, 1658 - id., 1738

Simon Demasso

(Lyon, 1658 - id., 1738

Charles-François Hutin

(Paris, 1715-Dresde, 1776)

Charles-François Hutin

(Paris, 1715-Dresde, 1776)

Louis Adrien MASRELIEZ

(Paris, 1748 - Stockholm, 1810)

Louis Adrien MASRELIEZ

(Paris, 1748 - Stockholm, 1810)

Pierre Peyron

(Aix-en-Provence, 1744 - Paris, 1814)

Pierre Peyron

(Aix-en-Provence, 1744 - Paris, 1814)

Philippe DEREUX

(Lyon, 1918 - Villeurbanne, 2001)

Philippe DEREUX

(Lyon, 1918 - Villeurbanne, 2001)

Robert MALAVAL

(Nice, 1937 - Paris, 1980)

Robert MALAVAL

(Nice, 1937 - Paris, 1980)

-165x133.jpg) Bernard REQUICHOT

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, 1929 - Paris, 1961)

Bernard REQUICHOT

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, 1929 - Paris, 1961)

Bernard REQUICHOT

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, Sarthe, 1929 – Paris, 1961)

Bernard REQUICHOT

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, Sarthe, 1929 – Paris, 1961)

Oskar Bergman

(Stockholm, 1879 – id., 1963)

Oskar Bergman

(Stockholm, 1879 – id., 1963)

Mélanie DELATTRE-VOGT

(Valenciennes, 1984)

Mélanie DELATTRE-VOGT

(Valenciennes, 1984)

Helmer Osslund

(Tuna, 1866 – Stockholm, 1938)

Helmer Osslund

(Tuna, 1866 – Stockholm, 1938)

Marcel ROUX

(Bessenay, 1878 – Chartres, 1922)

Marcel ROUX

(Bessenay, 1878 – Chartres, 1922)

Jules-Elie DELAUNAY

(Nantes, 1828 – Paris, 1891)

Jules-Elie DELAUNAY

(Nantes, 1828 – Paris, 1891)

Ernest Antoine Hebert

(Grenoble, 1817 – La Tronche, 1908)

Ernest Antoine Hebert

(Grenoble, 1817 – La Tronche, 1908)

Harald Jerichau

(Copenhague, 1851 – Rome, 1878)

Harald Jerichau

(Copenhague, 1851 – Rome, 1878)

Eugène Roger

(Sens, 1807 – Paris, 1840)

Eugène Roger

(Sens, 1807 – Paris, 1840)

-165x133.jpg) François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

-165x133.jpg) Alberto GIRONELLA

(Mexico, 1929 – Valle de Bravo (Mexique), 1999)

Alberto GIRONELLA

(Mexico, 1929 – Valle de Bravo (Mexique), 1999)

Nicolas-Antoine Taunay

(Paris, 1755 – id., 1830)

Nicolas-Antoine Taunay

(Paris, 1755 – id., 1830)

-165x133.jpg) François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

-165x133.jpg) Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld

(Carpentras, 1758 – Montmorency, 1846)

Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld

(Carpentras, 1758 – Montmorency, 1846)

-165x133.jpg) Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 – Paris, 1657)

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 – Paris, 1657)

Paris BORDONE

(Treviso, 1500 – Venice, 1571)

Paris BORDONE

(Treviso, 1500 – Venice, 1571)

-165x133.jpg) Raoul UBAC

(Malmedy or Cologne, 1910 – Dieudonné, 1985)

Raoul UBAC

(Malmedy or Cologne, 1910 – Dieudonné, 1985)

-165x133.jpg) Robert Malaval

(Nice, 1937 – Paris, 1980)

Robert Malaval

(Nice, 1937 – Paris, 1980)

Pierre Peyron

(Aix-en-Provence, 1744 – Paris, 1814)

Pierre Peyron

(Aix-en-Provence, 1744 – Paris, 1814)

Jules-Elie Delaunay

(Nantes, 1828 – Paris, 1891)

Jules-Elie Delaunay

(Nantes, 1828 – Paris, 1891)

Marcel Roux

(Bessenay, 1878 – Chartres, 1922)

Marcel Roux

(Bessenay, 1878 – Chartres, 1922)

-165x133.jpg) Alberto Gironella

(Mexico, 1929 – Valle de Bravo (Mexico), 1999) 32. El entierro de Zapata y ostros enterramientos [Funeral of Zapata and Other Burials], Elas de Oro II, 1972 A tribute to Zapata Alberto Gironella (1929-1999) had his first exhibition in 1952 in a gallery in

Alberto Gironella

(Mexico, 1929 – Valle de Bravo (Mexico), 1999) 32. El entierro de Zapata y ostros enterramientos [Funeral of Zapata and Other Burials], Elas de Oro II, 1972 A tribute to Zapata Alberto Gironella (1929-1999) had his first exhibition in 1952 in a gallery in

-165x133.jpg) Thomas Blanchet

(Paris, 1614 – Lyon, 1689)

Thomas Blanchet

(Paris, 1614 – Lyon, 1689)

Valentin Lefèvre

(Bruxelles, 1637 – Venise, 1677)

Valentin Lefèvre

(Bruxelles, 1637 – Venise, 1677)

Laurent Pécheux

Lyon, 1729 – Turin, 1821

Laurent Pécheux

Lyon, 1729 – Turin, 1821

Jean-Baptiste Deshays

(Rouen, 1729 – Paris, 1765)

Jean-Baptiste Deshays

(Rouen, 1729 – Paris, 1765)

Joseph François Ducq

(Ledeghem, 1762 – Bruges, 1829)

Joseph François Ducq

(Ledeghem, 1762 – Bruges, 1829)

Holger Drachmann

(Copenhague, 1846 – Hornbaek, 1908)

Holger Drachmann

(Copenhague, 1846 – Hornbaek, 1908)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 – id., 1947)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 – id., 1947)

Arthur George Walker

(Londres, 1861 – id., 1939)

Arthur George Walker

(Londres, 1861 – id., 1939)

Claude-Marie DUBUFE

(Paris, 1790 – Celle-Saint-Cloud, 1864)

Claude-Marie DUBUFE

(Paris, 1790 – Celle-Saint-Cloud, 1864)

-165x133.jpg) Nicolas Bertin

(Paris, 1668 – id., 1736)

Nicolas Bertin

(Paris, 1668 – id., 1736)

Vincent Bioulès

(Montpellier, 1938)

Vincent Bioulès

(Montpellier, 1938)

Paul Borel

(Lyon, 1828 – id., 1913)

Paul Borel

(Lyon, 1828 – id., 1913)

Giuseppe Cades

(Rome, 1750 – id., 1799)

Giuseppe Cades

(Rome, 1750 – id., 1799)

Andreas Joseph Chandelle

(Francfort, 1743-Id., 1820)

Andreas Joseph Chandelle

(Francfort, 1743-Id., 1820)

Émilie Charmy

(Saint Etienne, 1978 – Crosne, 1974)

Émilie Charmy

(Saint Etienne, 1978 – Crosne, 1974)

Michel Dorigny

(Saint-Quentin, 1616 – Paris, 1665)

Michel Dorigny

(Saint-Quentin, 1616 – Paris, 1665)

-165x133.jpg) Gustaf Fjaestad

(Stockholm, 1868 – Arvika, 1948)

Gustaf Fjaestad

(Stockholm, 1868 – Arvika, 1948)

François Gérard

(Rome, 1770 – Paris, 1837)

François Gérard

(Rome, 1770 – Paris, 1837)

Nicolas Henri Jeaurat de Bertry

(Paris, 1728 – id., vers 1796)

Nicolas Henri Jeaurat de Bertry

(Paris, 1728 – id., vers 1796)

Paul Jourdy

(Dijon, 1805 – Paris, 1856)

Paul Jourdy

(Dijon, 1805 – Paris, 1856)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 – Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, 1986)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 – Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, 1986)

Bernard Réquichot

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, Sarthe, 1929 – Paris, 1961)

Bernard Réquichot

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, Sarthe, 1929 – Paris, 1961)

Henri Michaux

(1899, Namur – 1984, Paris)

Henri Michaux

(1899, Namur – 1984, Paris)

Mario Alejandro Yllanes

(Oruro, 1913 – 1946 ?)

Mario Alejandro Yllanes

(Oruro, 1913 – 1946 ?)

Joseph-Benoît Suvée

(Bruges, 1743 – Rome, 1807)

Joseph-Benoît Suvée

(Bruges, 1743 – Rome, 1807)

-165x133.jpg) Joseph-Benoît Suvée

(Bruges, 1743 – Rome, 1807)

Joseph-Benoît Suvée

(Bruges, 1743 – Rome, 1807)

James Pradier

(Genève, 1790 – Bougival, 1852)

James Pradier

(Genève, 1790 – Bougival, 1852)

Pierre Révoil

(Lyon, 1776 – Paris, 1842)

Pierre Révoil

(Lyon, 1776 – Paris, 1842)

Jean-Baptiste Chatigny

(Lyon, 1834 – id., 1886)

Jean-Baptiste Chatigny

(Lyon, 1834 – id., 1886)

Louis Jean-François LAGRENEE, dit l’Aîné

(Paris, 1725 – Paris, 1805)

Louis Jean-François LAGRENEE, dit l’Aîné

(Paris, 1725 – Paris, 1805)

Michel-François Dandré-Bardon

Aix-en-Provence, 1700 – Paris, 1783

Michel-François Dandré-Bardon

Aix-en-Provence, 1700 – Paris, 1783

Hans Ditlev Martens

(Kiel, 1795 – Id., 1864)

Hans Ditlev Martens

(Kiel, 1795 – Id., 1864)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 – Id., 1947)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 – Id., 1947)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

Jeanne Bardey

(Lyon, 1872 - id., 1954)

Jeanne Bardey

(Lyon, 1872 - id., 1954)

André Utter

(Paris, 1886 - id., 1948)

André Utter

(Paris, 1886 - id., 1948)

Élisabeth Sonrel

(Tours, 1874 - Sceaux, 1953)

Élisabeth Sonrel

(Tours, 1874 - Sceaux, 1953)

Bernard Pruvost

(Alger, 1952)

Bernard Pruvost

(Alger, 1952)

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 - Paris, 1657)

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 - Paris, 1657)

Louis Cretey

(Lyon, before 1638 - Rome (?), after 1702)

Louis Cretey

(Lyon, before 1638 - Rome (?), after 1702)

Michel-François Dandré-Bardon

(Aix-en-Provence, 1700 - Paris, 1783)

Michel-François Dandré-Bardon

(Aix-en-Provence, 1700 - Paris, 1783)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 - Id., 1849)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 - Id., 1849)

Hans Ditlev Martens

(Kiel, 1795 - Kiel, 1864)

Hans Ditlev Martens

(Kiel, 1795 - Kiel, 1864)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 - Id., 1947)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 - Id., 1947)

Jeanne Bardey

(Lyon, 1872 - id., 1954)

Jeanne Bardey

(Lyon, 1872 - id., 1954)

André Utter

(Paris, 1886 – Id., 1948)

André Utter

(Paris, 1886 – Id., 1948)

Élisabeth Sonrel

Élisabeth Sonrel

Bernard Pruvost

(Algiers, 1952)

Bernard Pruvost

(Algiers, 1952)

Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg

(Sundeved, 1783 - Copenhague, 1853)

Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg

(Sundeved, 1783 - Copenhague, 1853)

Jean-François Forty (actif à Paris, 1775–90)

Jean-François Forty (actif à Paris, 1775–90)

Thomas Blanchet

(Paris, 1614 - Lyon, 1689)

Thomas Blanchet

(Paris, 1614 - Lyon, 1689)

Claude Nattiez

(actif à Rome entre 1641 et 1660)

Claude Nattiez

(actif à Rome entre 1641 et 1660)

Jean Charles Frontier

(Paris, 1701 – Lyon, 1763)

Jean Charles Frontier

(Paris, 1701 – Lyon, 1763)

Pierre Nicolas Legrand de Sérant

(Pont-l’Évêque, 1758 – Berne, 1829)

Pierre Nicolas Legrand de Sérant

(Pont-l’Évêque, 1758 – Berne, 1829)

Jean-Baptiste Isabey

(Nancy, 1767 – Paris, 1855)

Jean-Baptiste Isabey

(Nancy, 1767 – Paris, 1855)