Read more

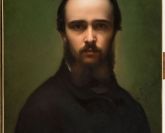

(Puerto Hincado, Santo Domingo, 1787 – Paris, 1872)

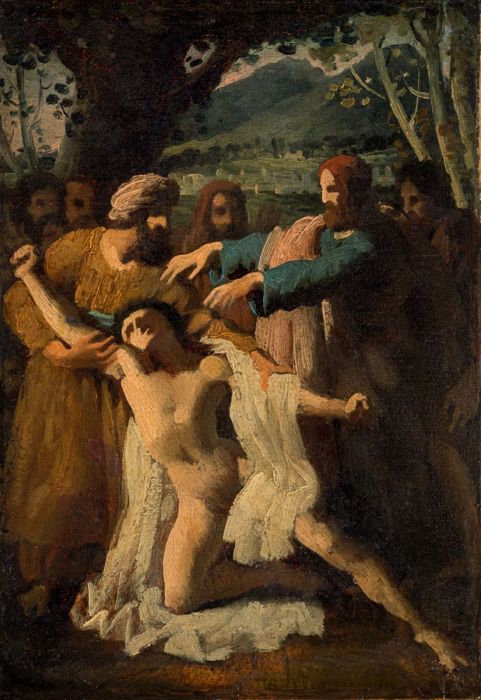

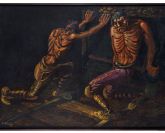

Christ Healing the Demoniac, sketch, c. 1817

Oil on paper mounted on canvas

21,5 x 15,3 cm

ill. 1. Henri-Joseph de Forestier, Christ Helaing the Demoniac, 1818, Oli on canvas, 308 x 215 cm, Cahors, musée Henri-Martin.

The highly unreliable civil status information catalogue entries and dictionaries have provided about this artist until recently betrays a lack of knowledge on the part of historians; his date of birth is variously given as 1787, 1790 and 1797, while he is alleged to have died in 1868, 1872, 1874 and 1892, either in Paris or Guadeloupe. Philippe Grunchec was the first to accurately pin down his birthdate, using the official accounts of the École des beaux-arts competitions, which all indicate that he was born in 1787. His burial certificate, dated December 1872, has cleared up all confusion as to the year of his death.1

Born into a well-off family of planters, Henri-Joseph de Forestier came to France before 1803, the year of his enrolment at the École des beaux-arts. A pupil of Vincent, and to a lesser extent of David, he won the first prize for history painting in 1813 and so became a resident at the French Academy in Rome the following year. He retained close links with Rome well after the end of his residency: in 1824 we find him in the company of self-taught artists living there, among them the painters Victor Schnetz and Léopold Robert, and the sculptors Paul Lemoyne et Jean- Baptiste Roman.2 His academic training completed, he obtained a number of public commissions and was made a Knight of the Legion of Honour in 1832. His output, however, was sparse and his appearances at the Salon irregular; indeed they ceased entirely in 1835 after he had been cited as a suspect in Fieschi’s attempted assassination of the king on 28 July, on the grounds that he had publicly expressed Republican opinions the same day.3 Politics brought him back into the public eye under the Second Republic: promoted to the rank of colonel in the 6th Legion of the National Guard in 1848, he nonetheless took part in the revolutionary demonstration of 13 June 1849, organised by the far left under Ledru-Rollin. He was arrested, but was subsequently acquitted by the High Court in Versailles,4 as he had been thirteen years earlier by the Chamber of Peers. Art’s low profile in this second part of his career – Forestier ended his life as mayor of Paris’s 6th arrondissement – suggests that the family fortune had put him out of harm’s way financially.

This sketch for Christ Healing the Demoniac is a reminder that early in his career he was considered one of the younger generation’s promising painters. While a resident at the Villa Médicis in Rome, however, he was tempted to distance himself from the academic norms, as can be seen in the over-reaction by members of the Academy in their analysis of his work: he showed “great vigour of feeling and execution”, but although his “eagerness to work well is powerfully apparent in every respect”,5 he needed to “quell the ardour that takes him beyond the boundaries of tasteful simplicity.”6 The subject of these commentaries was A Man Killing a Serpent, whose alleged surfeit of romanticism we cannot judge since its whereabouts are now unknown. However, in their contrasts of white gouache washes and brown ink the few drawings by Forestier that have come down to us suggest a community of vision with Géricault, Schnetz and Cogniet as these young artists sought to inject new energy into the classical vocabulary in the 1810s.7

In 1817, at the instigation of Charles Thévenin, the liberal-minded head of the French Academy, Forestier, together with his fellow resident Léon Pallière and the more senior Ingres, was invited to help decorate a chapel in the church of Trinità dei Monti, then in the course of restoration by the French ambassador, the Comte de Blacas. The theme – the life of Christ – left them free to choose their subjects, which were, respectively, the healing of a man possessed by the Devil, the Flagellation and Christ giving the keys to St Peter. Comparison of the three works – one in the museum in Cahors (ill. 1), the se cond in situ (see the sketch, ill. 2) and the third in the Ingres Museum (ill. 3) – highlights the originality of the Ingres, whose Nazarene sensibility was something totally new in French art; but Forestier’s picture stands out with an energetic severity recalling the early workshop of David and in particular the work of Jean-Germain Drouais.

Forestier’s small sketch presents many secondary variations in relation to the final picture: in the poses and in a background that was initially a landscape rather than an urban view. The most significant differences, though, are chromatic: the move from a nuanced palette to the brighter colours also to be found in Ingres’ and Pallière’s draperies suggests a deliberate harmonisation intended to give the chapel a radiance expressive of the pious French establishment’s urge towards restoration both material and spiritual.

Presented in Rome with the works of the other residents from 15 to 31 May 1818, Christ Healing the Demoniac was not shown in Paris until 1827, when it was given a favourable reception. Auguste Jal, among others, judged it “estimable, in the austere, simple genre of some of the Italian old masters in whose presence he composed and painted it.”8

1. Bellier and Auvray’s frequently incorrect dictionary gives his dates as 1790–1868. When the painting prizes were awarded at the École des beaux-arts in Paris on 21 August 1807, Forestier, who came in second, was stated to be twenty-one (Procès-verbal de la distribution générale des prix aux élèves des écoles spéciales du 21 août 1807 [Paris: Imprimerie impériale, 1807], p. 21); and at the ceremony in 1813, when he took out the First Rome Prize, his age was given as twenty-six (Revue encyclopédique: ou Analyse raisonnée des productions les plus remarquables dans la littérature, les sciences et les arts, [Paris: Imprimerie de J. B. Sajou, 1813], p. 417). For his date of burial, see État civil d’artistes francais; billets d’enterrement ou de décès depuis 1823 jusqu’à nos jours (Paris: Société de l’Histoire de l’art français, 1881), p. 112.

2. Étienne-Jean Delécluze, Carnet de route d’Italie (1823-1824). Impressions romaines, introduction and notes by Robert Baschet (Paris: Boivin, 1942), p. 102.

3. Comte de Portalis, Rapport fait à la Cour des Pairs - Attentat du 28 juillet 1835 (Paris: Imprimerie royale, 1835), p. 422.

4. Procès des accusés du 13 juin 1849 devant la Haute-Cour de justice (Paris: Ballard, 1849), passim.

5. Report by Guérin and Gros on the compulsory samples of work he sent to the Academy from Rome in 1817. See Catherine Giraudon (ed.), Procès-verbaux de l’Académie des Beaux-Arts, II: 1816-1820 (Paris: École des Chartes, 2002) p.179.

6. Report by Dupaty on the same samples, ibid. p. 516.

7. See, for example, The Wrath of Saul, Baltimore Museum of Fine Art, repr. in Jay Fisher and William Johnston (eds.), The Es sence of Line: French Drawings from Ingres to Degas, exh. cat. (Uni versity Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2005) no. 55, pp. 226-228 (entry by Philippe Bordes).

8. Auguste Jal, Esquisses, croquis, pochades, ou Tout ce qu’on voudra, sur le Salon de 1827 (Paris: Dupont; 1828), p. 494.

Shorten

Read more

Antoine Chintreuil

(1814 - 1873)

Antoine Chintreuil

(1814 - 1873)

Pierre Révoil

(Lyon 1776 – 1842)

Pierre Révoil

(Lyon 1776 – 1842)

Jacques-Louis David

(Paris, 1748 – Bruxelles, 1825)

Jacques-Louis David

(Paris, 1748 – Bruxelles, 1825)

Jean-Baptiste REGNAULT, Baron

Paris, 1754 – Id., 1829

Jean-Baptiste REGNAULT, Baron

Paris, 1754 – Id., 1829

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 – id., 1657)

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 – id., 1657)

Louis Adrien Masreliez

(Paris, 1748 – Stockholm, 1810)

Louis Adrien Masreliez

(Paris, 1748 – Stockholm, 1810)

Antoine Berjon

(Lyon, 1754 – id., 1838)

Antoine Berjon

(Lyon, 1754 – id., 1838)

Geer van Velde

(Lisse, 1898 – Cachan, 1977)

Geer van Velde

(Lisse, 1898 – Cachan, 1977)

Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld

(Carpentras, 1758 - Montmorency, 1846)

Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld

(Carpentras, 1758 - Montmorency, 1846)

Philippe-Auguste Hennequin

(Lyon, 1762 – Leuze, près de Tournai, 1833)

Philippe-Auguste Hennequin

(Lyon, 1762 – Leuze, près de Tournai, 1833)

Julien Adolphe Duvocelle

(Lille, 1873 – Corbeil-Essonnes, 1961)

Julien Adolphe Duvocelle

(Lille, 1873 – Corbeil-Essonnes, 1961)

François-Joseph Navez

(Charleroi, 1787 – Bruxelles, 1869)

François-Joseph Navez

(Charleroi, 1787 – Bruxelles, 1869)

Philippe-Auguste Immenraet

(Anvers, 1627 – id., 1679)

Philippe-Auguste Immenraet

(Anvers, 1627 – id., 1679)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonnard

(Grasse, 1780 – Paris, 1850)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonnard

(Grasse, 1780 – Paris, 1850)

Jeanne-Elisabeth Chaudet

(Paris, 1767 - id., 1832)

Jeanne-Elisabeth Chaudet

(Paris, 1767 - id., 1832)

Charles Barthélemy Jean Durupt

(Paris, 1804 - id., 1838)

Charles Barthélemy Jean Durupt

(Paris, 1804 - id., 1838)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonard

(Grasse, 1780 - Paris, 1850)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonard

(Grasse, 1780 - Paris, 1850)

Jean-Antoine Laurent

(Baccarat, 1736 - Epinal, 1832)

Jean-Antoine Laurent

(Baccarat, 1736 - Epinal, 1832)

Rafael Tejeo Diaz, dit Tejeo (ou Tegeo)

(Caravaca de la Cruz, Murcie, 1798 - Madrid, 1856)

Rafael Tejeo Diaz, dit Tejeo (ou Tegeo)

(Caravaca de la Cruz, Murcie, 1798 - Madrid, 1856)

Eric Forbes-Robertson

(Londres, 1865 – id., 1935)

Eric Forbes-Robertson

(Londres, 1865 – id., 1935)

Victor Orsel

(Oullins, 1795 – Paris, 1850)

Victor Orsel

(Oullins, 1795 – Paris, 1850)

François-Xavier Fabre

(Montpellier, 1766 – id., 1837)

François-Xavier Fabre

(Montpellier, 1766 – id., 1837)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 – Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, 1986)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 – Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, 1986)

Merry-Joseph Blondel

(Paris, 1781 – id., 1853)

Merry-Joseph Blondel

(Paris, 1781 – id., 1853)

Jean-Jacques Forty

(Marseille, 1743 – Aix-en-Provence, 1801)

Jean-Jacques Forty

(Marseille, 1743 – Aix-en-Provence, 1801)

François Eisen

(1695, Bruxelles – 1778, Paris)

François Eisen

(1695, Bruxelles – 1778, Paris)

Clément Jayet

(Langres, 1731 - Lyon, 1804)

Clément Jayet

(Langres, 1731 - Lyon, 1804)

Cornelis De Beer

(Utrecht, 1591 - Madrid, 1651)

Cornelis De Beer

(Utrecht, 1591 - Madrid, 1651)

Adam De Coster

(Malines, c. 1586, Antwerp, 1643)

Adam De Coster

(Malines, c. 1586, Antwerp, 1643)

Giovanni David

(Gabella Ligure, 1749 - Gênes, 1790)

Giovanni David

(Gabella Ligure, 1749 - Gênes, 1790)

Antoine Dubost

(Lyon, 769 - Paris, 1825)

Antoine Dubost

(Lyon, 769 - Paris, 1825)

Joseph Denis Odevaere

(Bruges, 1775 - Bruxelles, 1830)

Joseph Denis Odevaere

(Bruges, 1775 - Bruxelles, 1830)

Luca Giordano

(Naples, 1634 - id., 1705)

Luca Giordano

(Naples, 1634 - id., 1705)

Emile Didier

(Lyon, 1890 - id., 1965)

Emile Didier

(Lyon, 1890 - id., 1965)

Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret

(Bordeaux, 1782 - Paris, 1863)

Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret

(Bordeaux, 1782 - Paris, 1863)

André Bouys

(Hyères, 1656 - Paris, 1740)

André Bouys

(Hyères, 1656 - Paris, 1740)

Jacques-François Delyen

(Gand, 1684 - Paris, 1761)

Jacques-François Delyen

(Gand, 1684 - Paris, 1761)

-165x133.jpg) Jean-Jacques de Boissieu

(Lyon, 1736 - id., 1810)

Jean-Jacques de Boissieu

(Lyon, 1736 - id., 1810)

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux

(1827 - 1875)

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux

(1827 - 1875)

James Ensor

(Ostende, 1860 - id., 1949)

James Ensor

(Ostende, 1860 - id., 1949)

Jean Cocteau

(Maisons-Laffitte, 1889 - Milly-la-Forêt, 1963)

Jean Cocteau

(Maisons-Laffitte, 1889 - Milly-la-Forêt, 1963)

Antoine Demilly

(Mâcon, 1892 – Lyon, 1964)

Antoine Demilly

(Mâcon, 1892 – Lyon, 1964)

Charles Dukes

actif à Londres entre 1829 et 1865

Charles Dukes

actif à Londres entre 1829 et 1865

Crikor GARABÉTIAN

Bucarest, 1908 – Lyon, 1993

Crikor GARABÉTIAN

Bucarest, 1908 – Lyon, 1993

Pierre Tal-Coat [Pierre Jacob]

(Clohars-Carnoët, 1905 – Saint-Pierre-de-Bailleul, 1985)

Pierre Tal-Coat [Pierre Jacob]

(Clohars-Carnoët, 1905 – Saint-Pierre-de-Bailleul, 1985)

Pierre Molinier

(Agen, 1900 - Bordeaux, 1976)

Pierre Molinier

(Agen, 1900 - Bordeaux, 1976)

Patrice Giorda

né en 1952

Patrice Giorda

né en 1952

Frédéric Benrath

(Lyon, 1930 - Paris, 2007)

Frédéric Benrath

(Lyon, 1930 - Paris, 2007)

Félix Labisse

(Marchiennes (Nord), 1908 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1982)

Félix Labisse

(Marchiennes (Nord), 1908 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1982)

Bengt Lindström

(1925 - 2008)

Bengt Lindström

(1925 - 2008)

Bengt Lindström

(1925 - 2008)

Bengt Lindström

(1925 - 2008)

Jean-Batpiste Oudry

Paris, 1686 – Beauvais, 1755)

Jean-Batpiste Oudry

Paris, 1686 – Beauvais, 1755)

Albert Marquet

(Bordeaux, 1875 - Paris, 1947)

Albert Marquet

(Bordeaux, 1875 - Paris, 1947)

Balthasar K?OSSOWSKI DE ROLA, dit BALTHUS

(Paris, 1908 – Rossinière, 2001)

Balthasar K?OSSOWSKI DE ROLA, dit BALTHUS

(Paris, 1908 – Rossinière, 2001)

Gioavni Paolo Panini

(Plaisance, 1691 – Rome, 1765)

Gioavni Paolo Panini

(Plaisance, 1691 – Rome, 1765)

Alberto Savinio

(Athènes, 1891 - Rome, 1952)

Alberto Savinio

(Athènes, 1891 - Rome, 1952)

Oskar Bergman

(Stockholm, 1879 - id., 1963)

Oskar Bergman

(Stockholm, 1879 - id., 1963)

Léon Pourtau

(Bordeaux, 1868 - mort en mer, 1898)

Léon Pourtau

(Bordeaux, 1868 - mort en mer, 1898)

Jean-Baptiste Chatigny

(Lyon, 1834 - id., 1886)

Jean-Baptiste Chatigny

(Lyon, 1834 - id., 1886)

Adolphe Appian

(Lyon, 1814 – id., 1898)

Adolphe Appian

(Lyon, 1814 – id., 1898)

Paul Huet

(Paris, 1803 - id., 1869)

Paul Huet

(Paris, 1803 - id., 1869)

Fabius, dit Fabien Van Risamburgh

(Lyon, 1794 – Saint-Gengoux-le-National, Saône-et-Loire, 1866)

Fabius, dit Fabien Van Risamburgh

(Lyon, 1794 – Saint-Gengoux-le-National, Saône-et-Loire, 1866)

Jacques-Augustin Pajou

(Paris, 1766 b- id., 1828)

Jacques-Augustin Pajou

(Paris, 1766 b- id., 1828)

Louis Lafitte

(Paris, 1770 – id., 1828)

Louis Lafitte

(Paris, 1770 – id., 1828)

Louis Bélanger

(Paris, 1756 - Stockholm, 1816)

Louis Bélanger

(Paris, 1756 - Stockholm, 1816)

Claude Joseph Vernet

(Avignon, 1714 - Paris, 1799)

Claude Joseph Vernet

(Avignon, 1714 - Paris, 1799)

Joseph Wright of Derby

(Derby, 1734 – id., 1797)

Joseph Wright of Derby

(Derby, 1734 – id., 1797)

Claude-Joseph Vernet

(Avignon, 1714 – Paris, 1789)

Claude-Joseph Vernet

(Avignon, 1714 – Paris, 1789)

Philippe-Auguste Hennequin

(Luo, 1762 - Leuze, near Tournai, 1833)

Philippe-Auguste Hennequin

(Luo, 1762 - Leuze, near Tournai, 1833)

Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, known as Balthus

(Paris, 1908 - Rossinière, 2001)

Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, known as Balthus

(Paris, 1908 - Rossinière, 2001)

Jean-Baptiste Oudry

(Paris, 1686 - Beauvais, 1755)

Jean-Baptiste Oudry

(Paris, 1686 - Beauvais, 1755)

Jean Daret

(Brussels, 1614 - Paris, 1668)

Jean Daret

(Brussels, 1614 - Paris, 1668)

Jean Dubuffet

(Le Havre, 1901 - Paris, 1985)

Jean Dubuffet

(Le Havre, 1901 - Paris, 1985)

Fabius, known as Fabien van Risamburgh

(Lyon, 1794 - Saint-Gengoux-le-National, Saône-et-Loire, 1866)

Fabius, known as Fabien van Risamburgh

(Lyon, 1794 - Saint-Gengoux-le-National, Saône-et-Loire, 1866)

Gustave Moreau

(Paris, 1826 – id., 1898)

Gustave Moreau

(Paris, 1826 – id., 1898)

Rhin supérieur, entourage de Martin Schongauer ?

Rhin supérieur, entourage de Martin Schongauer ?

Giovanni Battista Castello, dit Il Bergamasco

(Crema, vers 1526 – El Escorial, 1569)

Giovanni Battista Castello, dit Il Bergamasco

(Crema, vers 1526 – El Escorial, 1569)

Giuseppe Antonio Pianca

Agnona, 1703 – Milano, 1762)

Giuseppe Antonio Pianca

Agnona, 1703 – Milano, 1762)

Pierre TAL-COAT (Pierre JACOB)

(Clohars-Carnoët, 1905 – Saint-Pierre-de-Bailleul, 1985)

Pierre TAL-COAT (Pierre JACOB)

(Clohars-Carnoët, 1905 – Saint-Pierre-de-Bailleul, 1985)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 - Rochetaillées-sur-Saône, 1986)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 - Rochetaillées-sur-Saône, 1986)

Camille Rogier

(1810-1896)

Camille Rogier

(1810-1896)

Paris BORDONE

(Trévise, 1500 - Venise, 1571)

Paris BORDONE

(Trévise, 1500 - Venise, 1571)

-165x133.jpg) Maître de l'Incrédulitgé de saint Thomas (Jean Ducamps ?)

Actif à Rome de la fin des années 1920 à 1637

Maître de l'Incrédulitgé de saint Thomas (Jean Ducamps ?)

Actif à Rome de la fin des années 1920 à 1637

-165x133.jpg) Claude Nattiez

(actif à Rome entre 1641 et 1660)

Claude Nattiez

(actif à Rome entre 1641 et 1660)

Simon Demasso

(Lyon, 1658 - id., 1738

Simon Demasso

(Lyon, 1658 - id., 1738

Charles-François Hutin

(Paris, 1715-Dresde, 1776)

Charles-François Hutin

(Paris, 1715-Dresde, 1776)

Louis Adrien MASRELIEZ

(Paris, 1748 - Stockholm, 1810)

Louis Adrien MASRELIEZ

(Paris, 1748 - Stockholm, 1810)

Pierre Peyron

(Aix-en-Provence, 1744 - Paris, 1814)

Pierre Peyron

(Aix-en-Provence, 1744 - Paris, 1814)

Philippe DEREUX

(Lyon, 1918 - Villeurbanne, 2001)

Philippe DEREUX

(Lyon, 1918 - Villeurbanne, 2001)

Robert MALAVAL

(Nice, 1937 - Paris, 1980)

Robert MALAVAL

(Nice, 1937 - Paris, 1980)

-165x133.jpg) Bernard REQUICHOT

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, 1929 - Paris, 1961)

Bernard REQUICHOT

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, 1929 - Paris, 1961)

Bernard REQUICHOT

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, Sarthe, 1929 – Paris, 1961)

Bernard REQUICHOT

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, Sarthe, 1929 – Paris, 1961)

Oskar Bergman

(Stockholm, 1879 – id., 1963)

Oskar Bergman

(Stockholm, 1879 – id., 1963)

Mélanie DELATTRE-VOGT

(Valenciennes, 1984)

Mélanie DELATTRE-VOGT

(Valenciennes, 1984)

Helmer Osslund

(Tuna, 1866 – Stockholm, 1938)

Helmer Osslund

(Tuna, 1866 – Stockholm, 1938)

Marcel ROUX

(Bessenay, 1878 – Chartres, 1922)

Marcel ROUX

(Bessenay, 1878 – Chartres, 1922)

Jules-Elie DELAUNAY

(Nantes, 1828 – Paris, 1891)

Jules-Elie DELAUNAY

(Nantes, 1828 – Paris, 1891)

Ernest Antoine Hebert

(Grenoble, 1817 – La Tronche, 1908)

Ernest Antoine Hebert

(Grenoble, 1817 – La Tronche, 1908)

Harald Jerichau

(Copenhague, 1851 – Rome, 1878)

Harald Jerichau

(Copenhague, 1851 – Rome, 1878)

Eugène Roger

(Sens, 1807 – Paris, 1840)

Eugène Roger

(Sens, 1807 – Paris, 1840)

-165x133.jpg) François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

-165x133.jpg) Alberto GIRONELLA

(Mexico, 1929 – Valle de Bravo (Mexique), 1999)

Alberto GIRONELLA

(Mexico, 1929 – Valle de Bravo (Mexique), 1999)

Nicolas-Antoine Taunay

(Paris, 1755 – id., 1830)

Nicolas-Antoine Taunay

(Paris, 1755 – id., 1830)

-165x133.jpg) François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

-165x133.jpg) Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld

(Carpentras, 1758 – Montmorency, 1846)

Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld

(Carpentras, 1758 – Montmorency, 1846)

-165x133.jpg) Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 – Paris, 1657)

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 – Paris, 1657)

Paris BORDONE

(Treviso, 1500 – Venice, 1571)

Paris BORDONE

(Treviso, 1500 – Venice, 1571)

-165x133.jpg) Raoul UBAC

(Malmedy or Cologne, 1910 – Dieudonné, 1985)

Raoul UBAC

(Malmedy or Cologne, 1910 – Dieudonné, 1985)

-165x133.jpg) Robert Malaval

(Nice, 1937 – Paris, 1980)

Robert Malaval

(Nice, 1937 – Paris, 1980)

Pierre Peyron

(Aix-en-Provence, 1744 – Paris, 1814)

Pierre Peyron

(Aix-en-Provence, 1744 – Paris, 1814)

Jules-Elie Delaunay

(Nantes, 1828 – Paris, 1891)

Jules-Elie Delaunay

(Nantes, 1828 – Paris, 1891)

Marcel Roux

(Bessenay, 1878 – Chartres, 1922)

Marcel Roux

(Bessenay, 1878 – Chartres, 1922)

-165x133.jpg) Alberto Gironella

(Mexico, 1929 – Valle de Bravo (Mexico), 1999) 32. El entierro de Zapata y ostros enterramientos [Funeral of Zapata and Other Burials], Elas de Oro II, 1972 A tribute to Zapata Alberto Gironella (1929-1999) had his first exhibition in 1952 in a gallery in

Alberto Gironella

(Mexico, 1929 – Valle de Bravo (Mexico), 1999) 32. El entierro de Zapata y ostros enterramientos [Funeral of Zapata and Other Burials], Elas de Oro II, 1972 A tribute to Zapata Alberto Gironella (1929-1999) had his first exhibition in 1952 in a gallery in

-165x133.jpg) Thomas Blanchet

(Paris, 1614 – Lyon, 1689)

Thomas Blanchet

(Paris, 1614 – Lyon, 1689)

Valentin Lefèvre

(Bruxelles, 1637 – Venise, 1677)

Valentin Lefèvre

(Bruxelles, 1637 – Venise, 1677)

Laurent Pécheux

Lyon, 1729 – Turin, 1821

Laurent Pécheux

Lyon, 1729 – Turin, 1821

Jean-Baptiste Deshays

(Rouen, 1729 – Paris, 1765)

Jean-Baptiste Deshays

(Rouen, 1729 – Paris, 1765)

Joseph François Ducq

(Ledeghem, 1762 – Bruges, 1829)

Joseph François Ducq

(Ledeghem, 1762 – Bruges, 1829)

Holger Drachmann

(Copenhague, 1846 – Hornbaek, 1908)

Holger Drachmann

(Copenhague, 1846 – Hornbaek, 1908)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 – id., 1947)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 – id., 1947)

Arthur George Walker

(Londres, 1861 – id., 1939)

Arthur George Walker

(Londres, 1861 – id., 1939)

Claude-Marie DUBUFE

(Paris, 1790 – Celle-Saint-Cloud, 1864)

Claude-Marie DUBUFE

(Paris, 1790 – Celle-Saint-Cloud, 1864)

-165x133.jpg) Nicolas Bertin

(Paris, 1668 – id., 1736)

Nicolas Bertin

(Paris, 1668 – id., 1736)

Vincent Bioulès

(Montpellier, 1938)

Vincent Bioulès

(Montpellier, 1938)

Paul Borel

(Lyon, 1828 – id., 1913)

Paul Borel

(Lyon, 1828 – id., 1913)

Giuseppe Cades

(Rome, 1750 – id., 1799)

Giuseppe Cades

(Rome, 1750 – id., 1799)

Andreas Joseph Chandelle

(Francfort, 1743-Id., 1820)

Andreas Joseph Chandelle

(Francfort, 1743-Id., 1820)

Émilie Charmy

(Saint Etienne, 1978 – Crosne, 1974)

Émilie Charmy

(Saint Etienne, 1978 – Crosne, 1974)

Michel Dorigny

(Saint-Quentin, 1616 – Paris, 1665)

Michel Dorigny

(Saint-Quentin, 1616 – Paris, 1665)

-165x133.jpg) Gustaf Fjaestad

(Stockholm, 1868 – Arvika, 1948)

Gustaf Fjaestad

(Stockholm, 1868 – Arvika, 1948)

François Gérard

(Rome, 1770 – Paris, 1837)

François Gérard

(Rome, 1770 – Paris, 1837)

Nicolas Henri Jeaurat de Bertry

(Paris, 1728 – id., vers 1796)

Nicolas Henri Jeaurat de Bertry

(Paris, 1728 – id., vers 1796)

Paul Jourdy

(Dijon, 1805 – Paris, 1856)

Paul Jourdy

(Dijon, 1805 – Paris, 1856)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 – Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, 1986)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 – Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, 1986)

Bernard Réquichot

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, Sarthe, 1929 – Paris, 1961)

Bernard Réquichot

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, Sarthe, 1929 – Paris, 1961)

Henri Michaux

(1899, Namur – 1984, Paris)

Henri Michaux

(1899, Namur – 1984, Paris)

Mario Alejandro Yllanes

(Oruro, 1913 – 1946 ?)

Mario Alejandro Yllanes

(Oruro, 1913 – 1946 ?)

Joseph-Benoît Suvée

(Bruges, 1743 – Rome, 1807)

Joseph-Benoît Suvée

(Bruges, 1743 – Rome, 1807)

-165x133.jpg) Joseph-Benoît Suvée

(Bruges, 1743 – Rome, 1807)

Joseph-Benoît Suvée

(Bruges, 1743 – Rome, 1807)

James Pradier

(Genève, 1790 – Bougival, 1852)

James Pradier

(Genève, 1790 – Bougival, 1852)

Pierre Révoil

(Lyon, 1776 – Paris, 1842)

Pierre Révoil

(Lyon, 1776 – Paris, 1842)

Jean-Baptiste Chatigny

(Lyon, 1834 – id., 1886)

Jean-Baptiste Chatigny

(Lyon, 1834 – id., 1886)

Louis Jean-François LAGRENEE, dit l’Aîné

(Paris, 1725 – Paris, 1805)

Louis Jean-François LAGRENEE, dit l’Aîné

(Paris, 1725 – Paris, 1805)

Michel-François Dandré-Bardon

Aix-en-Provence, 1700 – Paris, 1783

Michel-François Dandré-Bardon

Aix-en-Provence, 1700 – Paris, 1783

Hans Ditlev Martens

(Kiel, 1795 – Id., 1864)

Hans Ditlev Martens

(Kiel, 1795 – Id., 1864)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 – Id., 1947)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 – Id., 1947)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

Jeanne Bardey

(Lyon, 1872 - id., 1954)

Jeanne Bardey

(Lyon, 1872 - id., 1954)

André Utter

(Paris, 1886 - id., 1948)

André Utter

(Paris, 1886 - id., 1948)

Élisabeth Sonrel

(Tours, 1874 - Sceaux, 1953)

Élisabeth Sonrel

(Tours, 1874 - Sceaux, 1953)

Bernard Pruvost

(Alger, 1952)

Bernard Pruvost

(Alger, 1952)

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 - Paris, 1657)

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 - Paris, 1657)

Louis Cretey

(Lyon, before 1638 - Rome (?), after 1702)

Louis Cretey

(Lyon, before 1638 - Rome (?), after 1702)

Michel-François Dandré-Bardon

(Aix-en-Provence, 1700 - Paris, 1783)

Michel-François Dandré-Bardon

(Aix-en-Provence, 1700 - Paris, 1783)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 - Id., 1849)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 - Id., 1849)

Hans Ditlev Martens

(Kiel, 1795 - Kiel, 1864)

Hans Ditlev Martens

(Kiel, 1795 - Kiel, 1864)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 - Id., 1947)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 - Id., 1947)

Jeanne Bardey

(Lyon, 1872 - id., 1954)

Jeanne Bardey

(Lyon, 1872 - id., 1954)

André Utter

(Paris, 1886 – Id., 1948)

André Utter

(Paris, 1886 – Id., 1948)

Élisabeth Sonrel

Élisabeth Sonrel

Bernard Pruvost

(Algiers, 1952)

Bernard Pruvost

(Algiers, 1952)

Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg

(Sundeved, 1783 - Copenhague, 1853)

Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg

(Sundeved, 1783 - Copenhague, 1853)

Jean-François Forty (actif à Paris, 1775–90)

Jean-François Forty (actif à Paris, 1775–90)

Thomas Blanchet

(Paris, 1614 - Lyon, 1689)

Thomas Blanchet

(Paris, 1614 - Lyon, 1689)

Claude Nattiez

(actif à Rome entre 1641 et 1660)

Claude Nattiez

(actif à Rome entre 1641 et 1660)

Jean Charles Frontier

(Paris, 1701 – Lyon, 1763)

Jean Charles Frontier

(Paris, 1701 – Lyon, 1763)

Pierre Nicolas Legrand de Sérant

(Pont-l’Évêque, 1758 – Berne, 1829)

Pierre Nicolas Legrand de Sérant

(Pont-l’Évêque, 1758 – Berne, 1829)

Jean-Baptiste Isabey

(Nancy, 1767 – Paris, 1855)

Jean-Baptiste Isabey

(Nancy, 1767 – Paris, 1855)