Read more

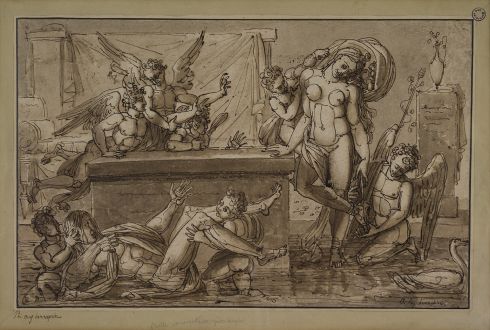

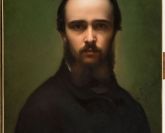

(Luo, 1762 - Leuze, near Tournai, 1833)

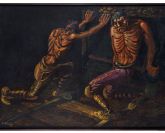

Venus at Her Bath

Pen and brown ink and wash, over traces of black chalk,

24.4 x 38 cm.

Signed lower right: Phi. Aug. hennequin and on the plinth: hennequin

Provenance

Collection des Garinières (collector’s stamp on mount, not in Lugt).

– Sale in Lyon, 1909.

– Galerie Didier Aaron in 1993.

Literature

Jérémie Benoit, Philippe-Auguste Hennequin (1762-1833) (Paris: Arthéna, 1994, no. D. 69, pp. 141–142, reproduced. (Ancient composition).

Attracted in his youth to the ferment of revolutionary ideas and driven by a rebellious temperament, Hennequin had an early career that can only be described as troubled. After training at the School of Drawing in Lyon under Donatien Nonotte and Eberhard Cogell, in late 1780 he enrolled at the atelier David had just opened in Paris; however, he was expelled the following year in the wake of a theft of paint for which he was denounced by his fellow student Wicar. He spent the years 1784–1789 in Rome, where he was pursued by the Papal police for his Masonic activities, a situation aggravated by his association with the subversive Count Cagliostro. Taking refuge in Lyon, he played an active part in the French Revolution on the Jacobin side, but had to flee the White Terror after the events of 9 Thermidor and the fall of Robespierre. On his return to Paris in 1796 he was condemned to life imprisonment for his part in the attempted insurrection at the Grenelle army camp, the final episode in the “Conspiracy of the Equals” and its intended overthrowing of the Convention, but was released in February 1797. In 1799 he achieved a succès d’estime – more political than critical – at the Salon with his monumental allegory Dix août (Tenth of August), a celebration of the fall of the monarchy financed buy the neo-Jacobin government and winner of a first prize from the French Institute. The painting was destroyed in 1820, but fragments can be found in the museums in Angers, Caen, Le Mans and Rouen. The critics reacted more favourably to his Remorse of Orestes at the Salon in 1800, a sweepingly energetic example of Classical romanticism showing Orestes pursued by the Furies after the murder of Clytemnestra (Paris, Musée du Louvre). However, unable to equal the virtuosity of his contemporaries and despairing of making a place for himself in France, he left for Belgium in 1809 and struggled to live by his art until he moved to Tournai in 1821.

After the Grenelle insurrection affair Hennequin had abandoned political activism to look after his personal interests and make a career for himself via the Salon. The mythological drawings he now undertook point up these concerns and his readiness to meet the tastes of the Directory clientele. Prepared on a number of sheets showing different episodes from the story of the two Trojan War heroes, Paris Leaving Helen to Fight Menelaus, shown at the Salon in 1798 (present location unknown), is the result of his exploration of the gracious genre. Together with Homer Reciting His Poetry (Paris, Musée du Louvre), this is his largest drawn composition from these years and the only truly erotic one. While the artist’s fondness for hermetic allegories

has discouraged any attempts at identifying its subject, there is little ambiguity here, and the subject can be linked to an image in favour during the Mannerist period: Venus bathing with Mars or Adonis. Primaticcio portrayed Venus and Mars in a lost composition probably intended for the baths at the Château de Fontainebleau, known by a drawing (see supra ill. 1, p. 40) and cited in an engraving by Antonio Fantuzzi: it shows the goddess wearing, as in Hennequin’s drawing, a flagrantly anecdotal turban and entering Mars’s bath. Venus and Adonis bathing is one of Giulio Romano’s subjects in the Cupid and Psyche room in the Palazzo del Te in Mantua (see supra ill. 2, p. 43). As in the latter picture, Hennequin shows numerous cupids preparing the lovers’ frolics.

The liberty of this composition is surprising for an artist who has nowhere else shown any interest in licentious subjects. In a whimsically personal interpretation of the fable, he reverses the roles, with Venus dominating from above the enforced passivity of a hero caught in the snakelike coils of a garment. Rarely in the case of this artist has the taste for anatomical schematization – the use of line overly segmenting the naked bodies and sheathing them with muscles – been so vigorously expressed; this reinforces the analogy of his disegno with that of the cinquecento. (M.K.)

Shorten

Read more

Antoine Chintreuil

(1814 - 1873)

Antoine Chintreuil

(1814 - 1873)

Pierre Révoil

(Lyon 1776 – 1842)

Pierre Révoil

(Lyon 1776 – 1842)

Jacques-Louis David

(Paris, 1748 – Bruxelles, 1825)

Jacques-Louis David

(Paris, 1748 – Bruxelles, 1825)

Jean-Baptiste REGNAULT, Baron

Paris, 1754 – Id., 1829

Jean-Baptiste REGNAULT, Baron

Paris, 1754 – Id., 1829

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 – id., 1657)

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 – id., 1657)

Louis Adrien Masreliez

(Paris, 1748 – Stockholm, 1810)

Louis Adrien Masreliez

(Paris, 1748 – Stockholm, 1810)

Antoine Berjon

(Lyon, 1754 – id., 1838)

Antoine Berjon

(Lyon, 1754 – id., 1838)

Geer van Velde

(Lisse, 1898 – Cachan, 1977)

Geer van Velde

(Lisse, 1898 – Cachan, 1977)

Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld

(Carpentras, 1758 - Montmorency, 1846)

Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld

(Carpentras, 1758 - Montmorency, 1846)

Philippe-Auguste Hennequin

(Lyon, 1762 – Leuze, près de Tournai, 1833)

Philippe-Auguste Hennequin

(Lyon, 1762 – Leuze, près de Tournai, 1833)

Julien Adolphe Duvocelle

(Lille, 1873 – Corbeil-Essonnes, 1961)

Julien Adolphe Duvocelle

(Lille, 1873 – Corbeil-Essonnes, 1961)

François-Joseph Navez

(Charleroi, 1787 – Bruxelles, 1869)

François-Joseph Navez

(Charleroi, 1787 – Bruxelles, 1869)

Philippe-Auguste Immenraet

(Anvers, 1627 – id., 1679)

Philippe-Auguste Immenraet

(Anvers, 1627 – id., 1679)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonnard

(Grasse, 1780 – Paris, 1850)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonnard

(Grasse, 1780 – Paris, 1850)

Jeanne-Elisabeth Chaudet

(Paris, 1767 - id., 1832)

Jeanne-Elisabeth Chaudet

(Paris, 1767 - id., 1832)

Charles Barthélemy Jean Durupt

(Paris, 1804 - id., 1838)

Charles Barthélemy Jean Durupt

(Paris, 1804 - id., 1838)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonard

(Grasse, 1780 - Paris, 1850)

Alexandre-Evariste Fragonard

(Grasse, 1780 - Paris, 1850)

Jean-Antoine Laurent

(Baccarat, 1736 - Epinal, 1832)

Jean-Antoine Laurent

(Baccarat, 1736 - Epinal, 1832)

Rafael Tejeo Diaz, dit Tejeo (ou Tegeo)

(Caravaca de la Cruz, Murcie, 1798 - Madrid, 1856)

Rafael Tejeo Diaz, dit Tejeo (ou Tegeo)

(Caravaca de la Cruz, Murcie, 1798 - Madrid, 1856)

Eric Forbes-Robertson

(Londres, 1865 – id., 1935)

Eric Forbes-Robertson

(Londres, 1865 – id., 1935)

Victor Orsel

(Oullins, 1795 – Paris, 1850)

Victor Orsel

(Oullins, 1795 – Paris, 1850)

François-Xavier Fabre

(Montpellier, 1766 – id., 1837)

François-Xavier Fabre

(Montpellier, 1766 – id., 1837)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 – Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, 1986)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 – Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, 1986)

Merry-Joseph Blondel

(Paris, 1781 – id., 1853)

Merry-Joseph Blondel

(Paris, 1781 – id., 1853)

Jean-Jacques Forty

(Marseille, 1743 – Aix-en-Provence, 1801)

Jean-Jacques Forty

(Marseille, 1743 – Aix-en-Provence, 1801)

François Eisen

(1695, Bruxelles – 1778, Paris)

François Eisen

(1695, Bruxelles – 1778, Paris)

Clément Jayet

(Langres, 1731 - Lyon, 1804)

Clément Jayet

(Langres, 1731 - Lyon, 1804)

Cornelis De Beer

(Utrecht, 1591 - Madrid, 1651)

Cornelis De Beer

(Utrecht, 1591 - Madrid, 1651)

Adam De Coster

(Malines, c. 1586, Antwerp, 1643)

Adam De Coster

(Malines, c. 1586, Antwerp, 1643)

Giovanni David

(Gabella Ligure, 1749 - Gênes, 1790)

Giovanni David

(Gabella Ligure, 1749 - Gênes, 1790)

Antoine Dubost

(Lyon, 769 - Paris, 1825)

Antoine Dubost

(Lyon, 769 - Paris, 1825)

Joseph Denis Odevaere

(Bruges, 1775 - Bruxelles, 1830)

Joseph Denis Odevaere

(Bruges, 1775 - Bruxelles, 1830)

Henri-Joseph Forestier

(Puerto Hincado, Santo Domingo, 1787 – Paris, 1872)

Henri-Joseph Forestier

(Puerto Hincado, Santo Domingo, 1787 – Paris, 1872)

Luca Giordano

(Naples, 1634 - id., 1705)

Luca Giordano

(Naples, 1634 - id., 1705)

Emile Didier

(Lyon, 1890 - id., 1965)

Emile Didier

(Lyon, 1890 - id., 1965)

Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret

(Bordeaux, 1782 - Paris, 1863)

Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret

(Bordeaux, 1782 - Paris, 1863)

André Bouys

(Hyères, 1656 - Paris, 1740)

André Bouys

(Hyères, 1656 - Paris, 1740)

Jacques-François Delyen

(Gand, 1684 - Paris, 1761)

Jacques-François Delyen

(Gand, 1684 - Paris, 1761)

-165x133.jpg) Jean-Jacques de Boissieu

(Lyon, 1736 - id., 1810)

Jean-Jacques de Boissieu

(Lyon, 1736 - id., 1810)

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux

(1827 - 1875)

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux

(1827 - 1875)

James Ensor

(Ostende, 1860 - id., 1949)

James Ensor

(Ostende, 1860 - id., 1949)

Jean Cocteau

(Maisons-Laffitte, 1889 - Milly-la-Forêt, 1963)

Jean Cocteau

(Maisons-Laffitte, 1889 - Milly-la-Forêt, 1963)

Antoine Demilly

(Mâcon, 1892 – Lyon, 1964)

Antoine Demilly

(Mâcon, 1892 – Lyon, 1964)

Charles Dukes

actif à Londres entre 1829 et 1865

Charles Dukes

actif à Londres entre 1829 et 1865

Crikor GARABÉTIAN

Bucarest, 1908 – Lyon, 1993

Crikor GARABÉTIAN

Bucarest, 1908 – Lyon, 1993

Pierre Tal-Coat [Pierre Jacob]

(Clohars-Carnoët, 1905 – Saint-Pierre-de-Bailleul, 1985)

Pierre Tal-Coat [Pierre Jacob]

(Clohars-Carnoët, 1905 – Saint-Pierre-de-Bailleul, 1985)

Pierre Molinier

(Agen, 1900 - Bordeaux, 1976)

Pierre Molinier

(Agen, 1900 - Bordeaux, 1976)

Patrice Giorda

né en 1952

Patrice Giorda

né en 1952

Frédéric Benrath

(Lyon, 1930 - Paris, 2007)

Frédéric Benrath

(Lyon, 1930 - Paris, 2007)

Félix Labisse

(Marchiennes (Nord), 1908 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1982)

Félix Labisse

(Marchiennes (Nord), 1908 - Neuilly-sur-Seine, 1982)

Bengt Lindström

(1925 - 2008)

Bengt Lindström

(1925 - 2008)

Bengt Lindström

(1925 - 2008)

Bengt Lindström

(1925 - 2008)

Jean-Batpiste Oudry

Paris, 1686 – Beauvais, 1755)

Jean-Batpiste Oudry

Paris, 1686 – Beauvais, 1755)

Albert Marquet

(Bordeaux, 1875 - Paris, 1947)

Albert Marquet

(Bordeaux, 1875 - Paris, 1947)

Balthasar K?OSSOWSKI DE ROLA, dit BALTHUS

(Paris, 1908 – Rossinière, 2001)

Balthasar K?OSSOWSKI DE ROLA, dit BALTHUS

(Paris, 1908 – Rossinière, 2001)

Gioavni Paolo Panini

(Plaisance, 1691 – Rome, 1765)

Gioavni Paolo Panini

(Plaisance, 1691 – Rome, 1765)

Alberto Savinio

(Athènes, 1891 - Rome, 1952)

Alberto Savinio

(Athènes, 1891 - Rome, 1952)

Oskar Bergman

(Stockholm, 1879 - id., 1963)

Oskar Bergman

(Stockholm, 1879 - id., 1963)

Léon Pourtau

(Bordeaux, 1868 - mort en mer, 1898)

Léon Pourtau

(Bordeaux, 1868 - mort en mer, 1898)

Jean-Baptiste Chatigny

(Lyon, 1834 - id., 1886)

Jean-Baptiste Chatigny

(Lyon, 1834 - id., 1886)

Adolphe Appian

(Lyon, 1814 – id., 1898)

Adolphe Appian

(Lyon, 1814 – id., 1898)

Paul Huet

(Paris, 1803 - id., 1869)

Paul Huet

(Paris, 1803 - id., 1869)

Fabius, dit Fabien Van Risamburgh

(Lyon, 1794 – Saint-Gengoux-le-National, Saône-et-Loire, 1866)

Fabius, dit Fabien Van Risamburgh

(Lyon, 1794 – Saint-Gengoux-le-National, Saône-et-Loire, 1866)

Jacques-Augustin Pajou

(Paris, 1766 b- id., 1828)

Jacques-Augustin Pajou

(Paris, 1766 b- id., 1828)

Louis Lafitte

(Paris, 1770 – id., 1828)

Louis Lafitte

(Paris, 1770 – id., 1828)

Louis Bélanger

(Paris, 1756 - Stockholm, 1816)

Louis Bélanger

(Paris, 1756 - Stockholm, 1816)

Claude Joseph Vernet

(Avignon, 1714 - Paris, 1799)

Claude Joseph Vernet

(Avignon, 1714 - Paris, 1799)

Joseph Wright of Derby

(Derby, 1734 – id., 1797)

Joseph Wright of Derby

(Derby, 1734 – id., 1797)

Claude-Joseph Vernet

(Avignon, 1714 – Paris, 1789)

Claude-Joseph Vernet

(Avignon, 1714 – Paris, 1789)

Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, known as Balthus

(Paris, 1908 - Rossinière, 2001)

Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, known as Balthus

(Paris, 1908 - Rossinière, 2001)

Jean-Baptiste Oudry

(Paris, 1686 - Beauvais, 1755)

Jean-Baptiste Oudry

(Paris, 1686 - Beauvais, 1755)

Jean Daret

(Brussels, 1614 - Paris, 1668)

Jean Daret

(Brussels, 1614 - Paris, 1668)

Jean Dubuffet

(Le Havre, 1901 - Paris, 1985)

Jean Dubuffet

(Le Havre, 1901 - Paris, 1985)

Fabius, known as Fabien van Risamburgh

(Lyon, 1794 - Saint-Gengoux-le-National, Saône-et-Loire, 1866)

Fabius, known as Fabien van Risamburgh

(Lyon, 1794 - Saint-Gengoux-le-National, Saône-et-Loire, 1866)

Gustave Moreau

(Paris, 1826 – id., 1898)

Gustave Moreau

(Paris, 1826 – id., 1898)

Rhin supérieur, entourage de Martin Schongauer ?

Rhin supérieur, entourage de Martin Schongauer ?

Giovanni Battista Castello, dit Il Bergamasco

(Crema, vers 1526 – El Escorial, 1569)

Giovanni Battista Castello, dit Il Bergamasco

(Crema, vers 1526 – El Escorial, 1569)

Giuseppe Antonio Pianca

Agnona, 1703 – Milano, 1762)

Giuseppe Antonio Pianca

Agnona, 1703 – Milano, 1762)

Pierre TAL-COAT (Pierre JACOB)

(Clohars-Carnoët, 1905 – Saint-Pierre-de-Bailleul, 1985)

Pierre TAL-COAT (Pierre JACOB)

(Clohars-Carnoët, 1905 – Saint-Pierre-de-Bailleul, 1985)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 - Rochetaillées-sur-Saône, 1986)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 - Rochetaillées-sur-Saône, 1986)

Camille Rogier

(1810-1896)

Camille Rogier

(1810-1896)

Paris BORDONE

(Trévise, 1500 - Venise, 1571)

Paris BORDONE

(Trévise, 1500 - Venise, 1571)

-165x133.jpg) Maître de l'Incrédulitgé de saint Thomas (Jean Ducamps ?)

Actif à Rome de la fin des années 1920 à 1637

Maître de l'Incrédulitgé de saint Thomas (Jean Ducamps ?)

Actif à Rome de la fin des années 1920 à 1637

-165x133.jpg) Claude Nattiez

(actif à Rome entre 1641 et 1660)

Claude Nattiez

(actif à Rome entre 1641 et 1660)

Simon Demasso

(Lyon, 1658 - id., 1738

Simon Demasso

(Lyon, 1658 - id., 1738

Charles-François Hutin

(Paris, 1715-Dresde, 1776)

Charles-François Hutin

(Paris, 1715-Dresde, 1776)

Louis Adrien MASRELIEZ

(Paris, 1748 - Stockholm, 1810)

Louis Adrien MASRELIEZ

(Paris, 1748 - Stockholm, 1810)

Pierre Peyron

(Aix-en-Provence, 1744 - Paris, 1814)

Pierre Peyron

(Aix-en-Provence, 1744 - Paris, 1814)

Philippe DEREUX

(Lyon, 1918 - Villeurbanne, 2001)

Philippe DEREUX

(Lyon, 1918 - Villeurbanne, 2001)

Robert MALAVAL

(Nice, 1937 - Paris, 1980)

Robert MALAVAL

(Nice, 1937 - Paris, 1980)

-165x133.jpg) Bernard REQUICHOT

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, 1929 - Paris, 1961)

Bernard REQUICHOT

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, 1929 - Paris, 1961)

Bernard REQUICHOT

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, Sarthe, 1929 – Paris, 1961)

Bernard REQUICHOT

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, Sarthe, 1929 – Paris, 1961)

Oskar Bergman

(Stockholm, 1879 – id., 1963)

Oskar Bergman

(Stockholm, 1879 – id., 1963)

Mélanie DELATTRE-VOGT

(Valenciennes, 1984)

Mélanie DELATTRE-VOGT

(Valenciennes, 1984)

Helmer Osslund

(Tuna, 1866 – Stockholm, 1938)

Helmer Osslund

(Tuna, 1866 – Stockholm, 1938)

Marcel ROUX

(Bessenay, 1878 – Chartres, 1922)

Marcel ROUX

(Bessenay, 1878 – Chartres, 1922)

Jules-Elie DELAUNAY

(Nantes, 1828 – Paris, 1891)

Jules-Elie DELAUNAY

(Nantes, 1828 – Paris, 1891)

Ernest Antoine Hebert

(Grenoble, 1817 – La Tronche, 1908)

Ernest Antoine Hebert

(Grenoble, 1817 – La Tronche, 1908)

Harald Jerichau

(Copenhague, 1851 – Rome, 1878)

Harald Jerichau

(Copenhague, 1851 – Rome, 1878)

Eugène Roger

(Sens, 1807 – Paris, 1840)

Eugène Roger

(Sens, 1807 – Paris, 1840)

-165x133.jpg) François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

-165x133.jpg) Alberto GIRONELLA

(Mexico, 1929 – Valle de Bravo (Mexique), 1999)

Alberto GIRONELLA

(Mexico, 1929 – Valle de Bravo (Mexique), 1999)

Nicolas-Antoine Taunay

(Paris, 1755 – id., 1830)

Nicolas-Antoine Taunay

(Paris, 1755 – id., 1830)

-165x133.jpg) François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

-165x133.jpg) Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld

(Carpentras, 1758 – Montmorency, 1846)

Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld

(Carpentras, 1758 – Montmorency, 1846)

-165x133.jpg) Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 – Paris, 1657)

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 – Paris, 1657)

Paris BORDONE

(Treviso, 1500 – Venice, 1571)

Paris BORDONE

(Treviso, 1500 – Venice, 1571)

-165x133.jpg) Raoul UBAC

(Malmedy or Cologne, 1910 – Dieudonné, 1985)

Raoul UBAC

(Malmedy or Cologne, 1910 – Dieudonné, 1985)

-165x133.jpg) Robert Malaval

(Nice, 1937 – Paris, 1980)

Robert Malaval

(Nice, 1937 – Paris, 1980)

Pierre Peyron

(Aix-en-Provence, 1744 – Paris, 1814)

Pierre Peyron

(Aix-en-Provence, 1744 – Paris, 1814)

Jules-Elie Delaunay

(Nantes, 1828 – Paris, 1891)

Jules-Elie Delaunay

(Nantes, 1828 – Paris, 1891)

Marcel Roux

(Bessenay, 1878 – Chartres, 1922)

Marcel Roux

(Bessenay, 1878 – Chartres, 1922)

-165x133.jpg) Alberto Gironella

(Mexico, 1929 – Valle de Bravo (Mexico), 1999) 32. El entierro de Zapata y ostros enterramientos [Funeral of Zapata and Other Burials], Elas de Oro II, 1972 A tribute to Zapata Alberto Gironella (1929-1999) had his first exhibition in 1952 in a gallery in

Alberto Gironella

(Mexico, 1929 – Valle de Bravo (Mexico), 1999) 32. El entierro de Zapata y ostros enterramientos [Funeral of Zapata and Other Burials], Elas de Oro II, 1972 A tribute to Zapata Alberto Gironella (1929-1999) had his first exhibition in 1952 in a gallery in

-165x133.jpg) Thomas Blanchet

(Paris, 1614 – Lyon, 1689)

Thomas Blanchet

(Paris, 1614 – Lyon, 1689)

Valentin Lefèvre

(Bruxelles, 1637 – Venise, 1677)

Valentin Lefèvre

(Bruxelles, 1637 – Venise, 1677)

Laurent Pécheux

Lyon, 1729 – Turin, 1821

Laurent Pécheux

Lyon, 1729 – Turin, 1821

Jean-Baptiste Deshays

(Rouen, 1729 – Paris, 1765)

Jean-Baptiste Deshays

(Rouen, 1729 – Paris, 1765)

Joseph François Ducq

(Ledeghem, 1762 – Bruges, 1829)

Joseph François Ducq

(Ledeghem, 1762 – Bruges, 1829)

Holger Drachmann

(Copenhague, 1846 – Hornbaek, 1908)

Holger Drachmann

(Copenhague, 1846 – Hornbaek, 1908)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 – id., 1947)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 – id., 1947)

Arthur George Walker

(Londres, 1861 – id., 1939)

Arthur George Walker

(Londres, 1861 – id., 1939)

Claude-Marie DUBUFE

(Paris, 1790 – Celle-Saint-Cloud, 1864)

Claude-Marie DUBUFE

(Paris, 1790 – Celle-Saint-Cloud, 1864)

-165x133.jpg) Nicolas Bertin

(Paris, 1668 – id., 1736)

Nicolas Bertin

(Paris, 1668 – id., 1736)

Vincent Bioulès

(Montpellier, 1938)

Vincent Bioulès

(Montpellier, 1938)

Paul Borel

(Lyon, 1828 – id., 1913)

Paul Borel

(Lyon, 1828 – id., 1913)

Giuseppe Cades

(Rome, 1750 – id., 1799)

Giuseppe Cades

(Rome, 1750 – id., 1799)

Andreas Joseph Chandelle

(Francfort, 1743-Id., 1820)

Andreas Joseph Chandelle

(Francfort, 1743-Id., 1820)

Émilie Charmy

(Saint Etienne, 1978 – Crosne, 1974)

Émilie Charmy

(Saint Etienne, 1978 – Crosne, 1974)

Michel Dorigny

(Saint-Quentin, 1616 – Paris, 1665)

Michel Dorigny

(Saint-Quentin, 1616 – Paris, 1665)

-165x133.jpg) Gustaf Fjaestad

(Stockholm, 1868 – Arvika, 1948)

Gustaf Fjaestad

(Stockholm, 1868 – Arvika, 1948)

François Gérard

(Rome, 1770 – Paris, 1837)

François Gérard

(Rome, 1770 – Paris, 1837)

Nicolas Henri Jeaurat de Bertry

(Paris, 1728 – id., vers 1796)

Nicolas Henri Jeaurat de Bertry

(Paris, 1728 – id., vers 1796)

Paul Jourdy

(Dijon, 1805 – Paris, 1856)

Paul Jourdy

(Dijon, 1805 – Paris, 1856)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 – Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, 1986)

Jean Raine

(Bruxelles, 1927 – Rochetaillée-sur-Saône, 1986)

Bernard Réquichot

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, Sarthe, 1929 – Paris, 1961)

Bernard Réquichot

(Asnières-sur-Vègre, Sarthe, 1929 – Paris, 1961)

Henri Michaux

(1899, Namur – 1984, Paris)

Henri Michaux

(1899, Namur – 1984, Paris)

Mario Alejandro Yllanes

(Oruro, 1913 – 1946 ?)

Mario Alejandro Yllanes

(Oruro, 1913 – 1946 ?)

Joseph-Benoît Suvée

(Bruges, 1743 – Rome, 1807)

Joseph-Benoît Suvée

(Bruges, 1743 – Rome, 1807)

-165x133.jpg) Joseph-Benoît Suvée

(Bruges, 1743 – Rome, 1807)

Joseph-Benoît Suvée

(Bruges, 1743 – Rome, 1807)

James Pradier

(Genève, 1790 – Bougival, 1852)

James Pradier

(Genève, 1790 – Bougival, 1852)

Pierre Révoil

(Lyon, 1776 – Paris, 1842)

Pierre Révoil

(Lyon, 1776 – Paris, 1842)

Jean-Baptiste Chatigny

(Lyon, 1834 – id., 1886)

Jean-Baptiste Chatigny

(Lyon, 1834 – id., 1886)

Louis Jean-François LAGRENEE, dit l’Aîné

(Paris, 1725 – Paris, 1805)

Louis Jean-François LAGRENEE, dit l’Aîné

(Paris, 1725 – Paris, 1805)

Michel-François Dandré-Bardon

Aix-en-Provence, 1700 – Paris, 1783

Michel-François Dandré-Bardon

Aix-en-Provence, 1700 – Paris, 1783

Hans Ditlev Martens

(Kiel, 1795 – Id., 1864)

Hans Ditlev Martens

(Kiel, 1795 – Id., 1864)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 – Id., 1947)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 – Id., 1947)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 – id., 1849)

Jeanne Bardey

(Lyon, 1872 - id., 1954)

Jeanne Bardey

(Lyon, 1872 - id., 1954)

André Utter

(Paris, 1886 - id., 1948)

André Utter

(Paris, 1886 - id., 1948)

Élisabeth Sonrel

(Tours, 1874 - Sceaux, 1953)

Élisabeth Sonrel

(Tours, 1874 - Sceaux, 1953)

Bernard Pruvost

(Alger, 1952)

Bernard Pruvost

(Alger, 1952)

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 - Paris, 1657)

Jacques Stella

(Lyon, 1596 - Paris, 1657)

Louis Cretey

(Lyon, before 1638 - Rome (?), after 1702)

Louis Cretey

(Lyon, before 1638 - Rome (?), after 1702)

Michel-François Dandré-Bardon

(Aix-en-Provence, 1700 - Paris, 1783)

Michel-François Dandré-Bardon

(Aix-en-Provence, 1700 - Paris, 1783)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 - Id., 1849)

François-Marius Granet

(Aix-en-Provence, 1775 - Id., 1849)

Hans Ditlev Martens

(Kiel, 1795 - Kiel, 1864)

Hans Ditlev Martens

(Kiel, 1795 - Kiel, 1864)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 - Id., 1947)

Pelle Swedlund

(Gävle, 1865 - Id., 1947)

Jeanne Bardey

(Lyon, 1872 - id., 1954)

Jeanne Bardey

(Lyon, 1872 - id., 1954)

André Utter

(Paris, 1886 – Id., 1948)

André Utter

(Paris, 1886 – Id., 1948)

Élisabeth Sonrel

Élisabeth Sonrel

Bernard Pruvost

(Algiers, 1952)

Bernard Pruvost

(Algiers, 1952)

Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg

(Sundeved, 1783 - Copenhague, 1853)

Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg

(Sundeved, 1783 - Copenhague, 1853)

Jean-François Forty (actif à Paris, 1775–90)

Jean-François Forty (actif à Paris, 1775–90)

Thomas Blanchet

(Paris, 1614 - Lyon, 1689)

Thomas Blanchet

(Paris, 1614 - Lyon, 1689)

Claude Nattiez

(actif à Rome entre 1641 et 1660)

Claude Nattiez

(actif à Rome entre 1641 et 1660)

Jean Charles Frontier

(Paris, 1701 – Lyon, 1763)

Jean Charles Frontier

(Paris, 1701 – Lyon, 1763)

Pierre Nicolas Legrand de Sérant

(Pont-l’Évêque, 1758 – Berne, 1829)

Pierre Nicolas Legrand de Sérant

(Pont-l’Évêque, 1758 – Berne, 1829)

Jean-Baptiste Isabey

(Nancy, 1767 – Paris, 1855)

Jean-Baptiste Isabey

(Nancy, 1767 – Paris, 1855)